Wed 29 Jul, 2009

Beth Short’s Birthday

Comments (0) Filed under: EventsTags: 1940s, Black Dahlia, Elizabeth Short, Esotouric, murder, WWII

Beth Short

Beth Short (aka “The Black Dahlia”) would have been 85 years old today.

It’s difficult for me to imagine her as anything other than a lonely, melancholy, enigma of a girl trying to navigate the frequently treacherous streets of postwar Los Angeles searching for someone to take care of her. Someone to love. During the late 1940s there were countless numbers of girls like Beth who were trying to find their way to different dreams: Hollywood stardom for some, and for others a cottage with a white picket fence, a loving husband and beautiful children.

If anything, the mystery of her murder has deepened since January 15, 1947 when her body was discovered on a vacant lot in Leimert Park. Her killer has never been positively identified. There have always been theories, ranging from the ridiculous to the sublime. The truth is that we’ll never really know for certain who murdered her. But if we can’t bring her killer to justice, maybe the best we can do is to learn something of Beth’s life and by so doing, we can honor her memory.

Beth at Camp Cooke

Beth was one of thousands of young women who had flocked to Los Angeles during, and immediately following, WWII. There were good times to be had drinking and dancing with soliders, sailors and, Beth’s favorite, pilots. But the city was also a dark and dangerous place to be. Many of the former soliders returned to civilian life with demons that could not be vanquished with a bottle of beer or a spin on the dance floor with a lovely girl.

Beth was one of thousands of young women who had flocked to Los Angeles during, and immediately following, WWII. There were good times to be had drinking and dancing with soliders, sailors and, Beth’s favorite, pilots. But the city was also a dark and dangerous place to be. Many of the former soliders returned to civilian life with demons that could not be vanquished with a bottle of beer or a spin on the dance floor with a lovely girl.

Because of my passion for vintage cosmetics and historic crime, I became interested in Beth’s makeup after reading comments made about her by one of her former roommates, Linda Rohr. Linda was 22 years old, and worked in the Rouge Room at Max Factor in Hollywood. When she was asked about Beth, Linda had said: “She had pretty blue eyes but sometimes I think she overdid with make-up an inch thick.” Linda went on to say that the effect of Beth’s makeup was startling, that she resembled a Geisha.

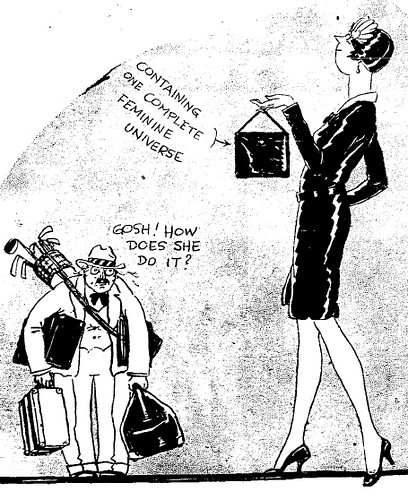

Makeup in the 1940s emphasized a natural look, and it seemed from Linda’s statement that Beth was applying her makeup contrary to the latest trends — something that women in their 20s seldom did. I began to wonder; what was Beth hiding? She wasn’t concealing a physical defect, she had lovely skin and as Linda had noted, pretty blue eyes. It struck me that Beth was subconciously using makeup as a mask — a way to keep the world at arm’s length and to become the character she needed to be in order to go out and hustle for drinks, dinner, or a place to stay.

For more information and insights into Beth’s last couple of weeks in Los Angeles, including the REAL last place that she was seen alive (no, NOT the Biltmore Hotel) join me on Esotouric’s The Real Black Dahlia tour this Saturday, August 1, 2009. Kim Cooper will tell you about the news coverage of the case, especially as reported by legendary newswoman, Aggie Underwood. Richard Schave will have tales to tell, and I’ll expand upon my personality sketch of Beth. Our special guest, Marcie Morgan-Gilbert, will treat tour goers to a look at fashion from 1940s.

For more information and insights into Beth’s last couple of weeks in Los Angeles, including the REAL last place that she was seen alive (no, NOT the Biltmore Hotel) join me on Esotouric’s The Real Black Dahlia tour this Saturday, August 1, 2009. Kim Cooper will tell you about the news coverage of the case, especially as reported by legendary newswoman, Aggie Underwood. Richard Schave will have tales to tell, and I’ll expand upon my personality sketch of Beth. Our special guest, Marcie Morgan-Gilbert, will treat tour goers to a look at fashion from 1940s.

Esotouric is the Los Angeles based, family run, tour company that was founded by the husband and wife team Kim Cooper and Richard Schave.

Twenty-four year old Gene Anderson was a lingerie designer , so she she took a particular interest in current fashion, and she loved to wear expensive clothes.

Twenty-four year old Gene Anderson was a lingerie designer , so she she took a particular interest in current fashion, and she loved to wear expensive clothes.

Upon being searched by a matron at the County Jail, it was discovered that Gene was packing a loaded revolver in her vanity bag!

Upon being searched by a matron at the County Jail, it was discovered that Gene was packing a loaded revolver in her vanity bag!