Mon 29 Dec, 2014

Duska Face Powder Box

Comments (0) Filed under: LOS ANGELES MAGAZINETags: Anais Nin, Ernest Hemmingway, Exposition des Arts Decoratifs, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Grank Graham Holmes, Henry and June, Lenox china, Rene Lalique, Theatre des Champs-Elysees, United Drug Company

The exquisite Duska face powder box (c. 1928) is one of the first I ever acquired. I had seen a photo of it in a book on collecting ladies’ compacts, so when I found it years later at a vintage textiles sale I was thrilled. It was as stunning in person as I’d hoped it would be. The box’s oval shape accommodates the length and breadth of the fountain, allowing it enough space to make a statement. Its bright red color was meant to catch the eye of a woman looking for something modern and sophisticated.

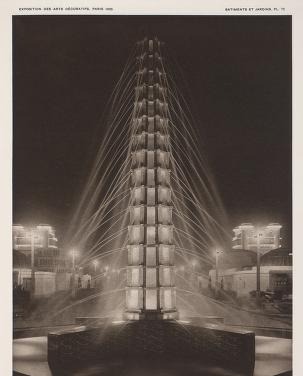

I was initially under the impression that the box had been created, like most of the items in my collection vintage cosmetics ephemera, by an anonymous graphic artist as a tribute to the fountain designed by Rene Lalique for the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs held in Paris in 1925. I discovered however that the back story on the Duska box is unique because was conceived by well-known artist Frank Graham Holmes, the chief designer of Lenox china from 1905 to 1954.The United Drug Company hired Holmes to design Duska for their chain of Rexall Drug Stores.

I was initially under the impression that the box had been created, like most of the items in my collection vintage cosmetics ephemera, by an anonymous graphic artist as a tribute to the fountain designed by Rene Lalique for the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs held in Paris in 1925. I discovered however that the back story on the Duska box is unique because was conceived by well-known artist Frank Graham Holmes, the chief designer of Lenox china from 1905 to 1954.The United Drug Company hired Holmes to design Duska for their chain of Rexall Drug Stores.

I feel strongly that in 1926 when Holmes drew the “Fountain” pattern for Lenox, he deliberately chose to pay homage to Lalique. Holmes’ design for the china, and subsequently this powder box, is a blend of bright colors (a hallmark of Art Deco) and a traditional floral theme, with graceful cascades of water flowing in a precise geometry. If not patterned after Lalique’s exposition fountain, Holmes’ Duska creation is similar enough to a glass panel designed by Lalique to be its twin.

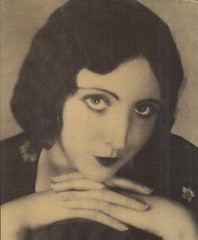

Which is why, no matter how the fountain concept originated, for me it will always evoke Paris during the 1920s. It would have been an exciting place to be, with a cast of characters one can only read about now: Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. (Had I been there then, surely I would be involved in a steamy assignation a la Anais Nin and Henry Miller, and I would make it a point to catch Josephine Baker’s infamous “banana dance” at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.)

Fortunately there are ways in which to vicariously experience an expatriate’s life in Paris during the 1920s, You can read Hemmingway’s or Fitzgerald’s novels, Anais Nin’s diaries or erotica, Henry Miller’s novel “Quiet Days in Clichy” (which I love) or rent the 1988 film “The Moderns” or the 1990 film “Henry and June” (based upon a portion of Nin’s diaries). For me, looking at this Duska powder box does the trick.

NOTE: To view the original post visit the Vintage Powder Room archive at Los Angeles Magazine.