The Guerlain advertisement by Jacques Darcy is one that I adore, and one which I have noticed is very similar to the Man Ray photograph of Elizabeth “Lee” Miller from 1930.

Elizabeth "Lee Miller" by Man Ray (1930)

Both images are of a woman’s face — upside down, hair flowing, eyes shut. The images reveal women who appear to be sleeping peacefully. Because the advertisement has a caption, we know that the woman is dreaming. The father of modern psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, said that “wish-fulfillment is the meaning of each and every dream, and hence there can be no dreams besides wishful dreams”. Nothing like interjecting a bit of Freudian psychology into an advertisement for lipstick!

Man Ray may not have been probing the human psyche in the same ways as Freud, but he was exploring the landscape of the mind through his art. Ray was an American artist residing in New York in 1916 when he became acquainted with fellow artists, and recent arrivals from France, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia. The three men were kindred spirits and they soon became active in the anti-art movement in the U.S. Anti-art didn’t mean that they rejected art per se but rather that they were rebelling against conventional “museum art”. The movement was known as Dada and was a protest against the nationalism, capitalism, and other “isms” which many people felt were the fundamental causes of World War I. Artist George Grosz characterized his Dadaist art as a protest “against this world of mutual destruction”.

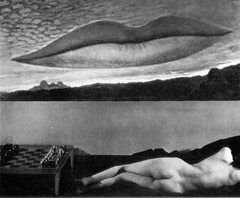

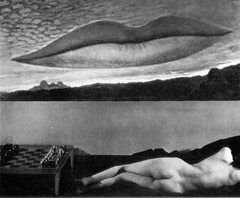

Observatory - The Lovers by Man Ray (1934)

When Ray arrived in France in 1921 he was one of many expatriate artists and writers who would gravitate to Paris in the 1920s; and just as his predecessors had done he found his way to Montparnasse, sometimes referred to as the “Harlem of Paris”. Ray continued to pursue his art; however, Dadaism peaked by 1922 as many of his contemporaries embraced Surrealism.

La Magie Noire by Rene Magritte

There were several parallel, and very important, art, design, philosophical, and political movements gaining ground during the 1920s: Dada, Surrealism, Art Deco, Freudian psychoanalysis, and Existentialism (the term existentialism was not used in the 1920s; it was coined in 1943 by Gabriel Marcel, and it would be retroactively applied to philosophers such as Martin Heideggar and Soren Kierkegaard). I see subtle similarities between the Darcy ad and the painting La Magie Noire by Rene Magritte. Perhaps it is the coloration, or the peaceful expression on the face of the woman who seems to belong to both the earth and the clouds.

For most of the 1920s Ray’s muse was Alice Prin (aka Kiki de Montparnasse), the Queen of Montparnasse. Kiki had come up hard as the illegitimate child of a peasant girl, and was given over to her grandmother to be raised. The two struggled in extreme poverty (Kiki often stole food from local gardens) and so when at age 12 she had an opportunity to live with her mother in Paris, she took it. She was a headstrong girl and she and her mother frequently clashed. When Kiki finally left her mother’s home for the last time she was only 14 years old.

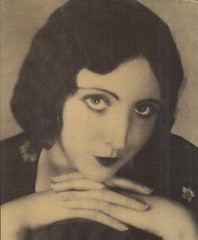

Kiki with vase by J. Mandel (c. 1928)

She was a lovely girl, and it wasn’t surprising that she was quickly discovered by local artists. Her relationship with the artists was often mutually beneficial — many times they produced their best work when using Kiki as a model. That was certainly true of Man Ray.

Kiki fled Paris in 1940 when the Germans began their occupation and she never returned as a resident. She died at age 51 — the likely result of alcoholism and drug abuse.

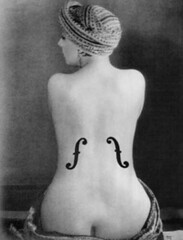

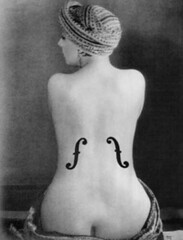

Le Violon d'Ingres by Man Ray (Kiki as model)

In 1929 Kiki was supplanted in Ray’s affections by Elizabeth “Lee” Miller. Lee arrived at Ray’s Paris studio and announced to him that she was his new student. He insisted that he didn’t accept apprentices, but Lee was extraordinary; she was gorgeous and talented. They became lovers as well as student and teacher. Lee had run to Paris after posing for a Kotex ad. The ad is famous for being the first feminine hygiene ad in which an actual photograph of a woman was used. At first Lee was mortified by the ad, apparently she hadn’t realized that she wasn’t to be a model for a drawing, but rather for a photograph.

Lee Miller in Kotex ad (1928)

Lee would stay with Man Ray for a few years, but eventually she grew restless and returned to New York where she opened her own studio. If her studio work was superlative, her work as a photojournalist for Vogue magazine during World War II was brilliant; however, witnessing scenes at liberated death camps, among other horrors, profoundly changed her.

She put away her camera in the 1950s and channeled her restless energy into gourmet cooking, at which she excelled. Lee succumbed to cancer in 1977; her ashes were scattered over her herb garden at her farm in Sussex, England.

Darcy ad for Guerlain's "Are You Her Type?" ad campaign

As for Jacques Darcy, the artist who created the distinctive advertisements for Guerlain, I have not been able to discover very much about him. I found conflicting information in various sources. The consensus seems to be that he was born on February 7, 1892 and died in 1963 in Michigan. His work appeared frequently during the 1920s and 1930s in such publications as Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. He is best known for the art he produced for Guerlain — in my opinion some of the best commercial art ever created.

From 1920 to 1955, Central Avenue was the L.A. equivalent of Harlem, where boogie woogie, jazz, and R&B were blasted from juke box speakers through the wee hours of the morning. The avenue was known as “the heart of Saturday night Los Angeles.” One of the classiest places to go for an evening’s revelry was the Dunbar Hotel, L.A.’s answer to the Savoy and Cotton Club in New York. In its heyday the Dunbar was the hub of African American culture in L.A., and it offered entertainment from such artists as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and Cab Calloway.

From 1920 to 1955, Central Avenue was the L.A. equivalent of Harlem, where boogie woogie, jazz, and R&B were blasted from juke box speakers through the wee hours of the morning. The avenue was known as “the heart of Saturday night Los Angeles.” One of the classiest places to go for an evening’s revelry was the Dunbar Hotel, L.A.’s answer to the Savoy and Cotton Club in New York. In its heyday the Dunbar was the hub of African American culture in L.A., and it offered entertainment from such artists as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and Cab Calloway.