Fri 29 Jan, 2016

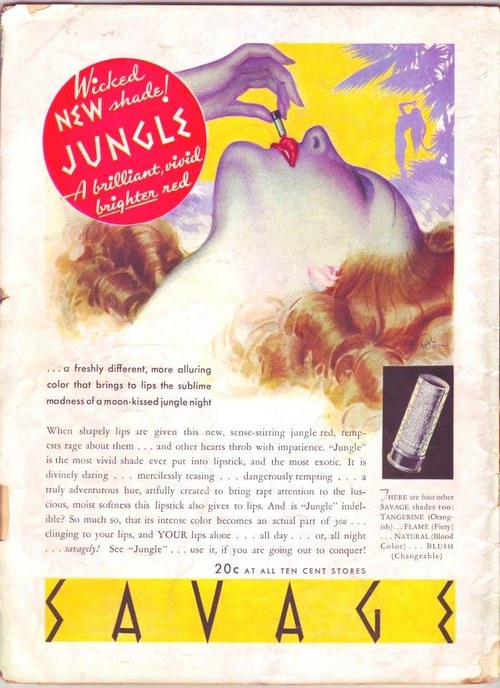

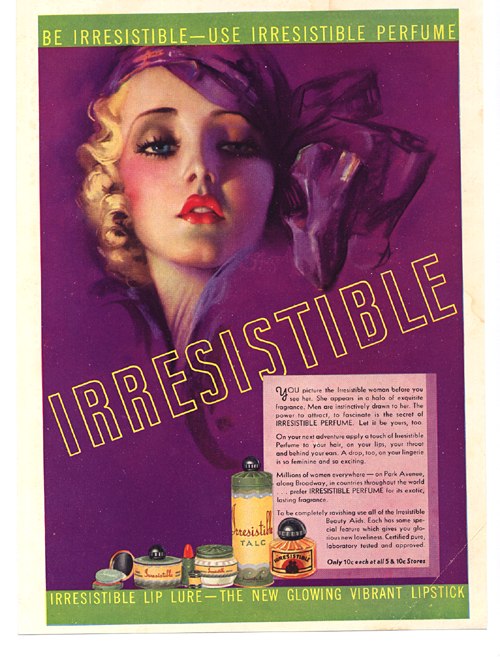

I have always been drawn to the Irresistible cosmetics ads because, well, they truly are irresistible. The colors are lush and the ads depict women who are individual beauties, not cookie cutter glamour girls.

I have always been drawn to the Irresistible cosmetics ads because, well, they truly are irresistible. The colors are lush and the ads depict women who are individual beauties, not cookie cutter glamour girls.

It is rare to discover the identity of an artist working in cosmetics advertising—their art is generally unsigned and they are often employed by the container company or the cosmetics manufacturer who wants the focus placed on the product, not the artist.

The unique renderings of the women in the Irresistible ads are so compelling, though, that I had to seek out the artist. Fortunately the Internet has made such spur-of-the-moment quests possible and within a few keystrokes I had a name: Zoe Mozert.

Zoe Mozert worked as a commercial artist during the 1930s, creating the dreamy, romanticized images for Irresistible, and she was also one of the few women working as a pin-up artist.

Zoe Mozert worked as a commercial artist during the 1930s, creating the dreamy, romanticized images for Irresistible, and she was also one of the few women working as a pin-up artist.

Mozert was attractive enough to be a pin-up girl herself and frequently posed in front of her camera for early selfies, which enabled her to be the model for her own drawings.

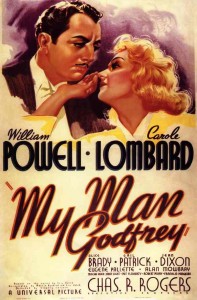

Zoe eventually moved from the East Coast to Hollywood, where her portraits of stars such as Joan Crawford, Myrna Loy, and Jean Harlow graced the covers of movie magazines. Mozert was also in demand as a movie poster artist. Her design for the 1937 comedy True Confessions might be her best, but my favorite is the one she created for the 1943 Howard Hughes horse opera The Outlaw, the film that introduced newcomer Jane Russell to audiences as the seductive Rio McDonald. Russell’s talent made her an actress, but I believe that it was Zoe’s depiction of her in the notorious poster that made her a star.