Fri 6 Nov, 2009

IRRESISTIBLE LIPSTICK

Comments (0) Filed under: LipstickTags: 1930s, 1940s, alcoholism, Clifford Odets, Jessica Lange, Kill Bill, Kurt Cobain, lobotomy, mental illness, Quentin Tarantino, Seattle, Uma Thurman, Western State Hospital

In her false witness, we hope you’re still with us,

To see if they float or drown

Our favorite patient, a display of patience,

Disease-covered Puget Sound

She’ll come back as fire, to burn all the liars,

And leave a blanket of ash on the ground

I miss the comfort in being sad

— from “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle” by Kurt Cobain

There’s something about the woman on this lipstick card that reminds me of the actress Frances Farmer. Maybe it’s the caption as much as it is the picture.

Frances Farmer was an absolutely gorgeous blonde who first hit the newspapers when, as a drama student at the University of Washington in Seattle in April 1935, she won first prize in a subscription contest sponsored by a local radical labor newspaper “The Voice of Action”. The prize for winning the contest was a six week trip via ocean liner to Soviet Russia to see a production at the Moscow Arts Theater. Frances’ mother Lillian wasn’t thrilled about the trip, and she told reporters “There has been no break between Frances and me over the trip. My fight is with the Voice of Action for sending her to Russia where she will be thrown in full contact with people who will probably make every effort to persuade her to Communism.”

Frances Farmer was an absolutely gorgeous blonde who first hit the newspapers when, as a drama student at the University of Washington in Seattle in April 1935, she won first prize in a subscription contest sponsored by a local radical labor newspaper “The Voice of Action”. The prize for winning the contest was a six week trip via ocean liner to Soviet Russia to see a production at the Moscow Arts Theater. Frances’ mother Lillian wasn’t thrilled about the trip, and she told reporters “There has been no break between Frances and me over the trip. My fight is with the Voice of Action for sending her to Russia where she will be thrown in full contact with people who will probably make every effort to persuade her to Communism.”

Frances wasn’t necessarily persuaded to embrace Communism, but she became even more determined to pursue an acting career. She returned to the U.S. during the summer of 1935, and her first stop was New York where she sought to launch a career in the theater. What she found instead was a Paramount Pictures talent scout, Oscar Serlin (credited with discovering Fred MacMurray). Frances did so well in her screen test that she was signed to a seven year contract on her 22nd birthday, and she promptly moved to Hollywood.

While Frances had more than enough talent for Hollywood she never had the temperament. She was headstrong (as evidenced by her trip to Russia against her parents wishes), and she had very little tolerance for the studio system which was firmly in place during the 1930s. Under the studio system every aspect of an actor’s life was managed — not the kind of arrangement designed to bring out the best in Frances. She was quoted as saying “Hollywood is a madhouse. It consumes ambitious youngsters. There’s no time to consider anyone. Hollywood casts you, forces you, pushes you. If you survive you’re plain lucky.”

Very early on the studio machine began to spin the story of Frances’ trip to Russia into something less likely to draw negative attention to her, or her political leanings. Initial reports stated the truth, that Frances had won first prize in a subsciptions contest for Voice of Action — but immediately following her arrival in Hollywood the story was retold very creatively with Frances winning a trip to Europe as the first prize in a popularity contest!

Paramount didn’t realize that they had a tiger by the tail. Frances arrived in Hollywood in September 1935, and by February 1936 she’d eloped to Yuma, Arizona with fellow actor William Wycliffe Anderson (aka Leif Erickson). Friends said they were surprised by the elopement and Frances’ mother Lillian said she was “completely floored”.

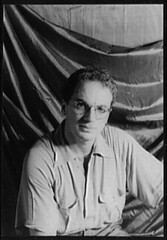

Clifford Odets c. 1937

In 1937 Frances left her husband at home and went off to Connecticut to work in summer stock. There she was invited to appear in Clifford Odets’ play “Golden Boy”. As were many people in the 1930s, Odets was a Marxist and his work reflected his politics. Ironically, when called before the House on Un-American Activities in 1952, Odets avoided being blacklisted by disavowing his past Communist affiliations and naming names.

Clifford and Frances had an affair while she was in New York; however, he was married to Acadamey Award winning actress Luise Ranier and he refused to leave her. Frances and Luise had more in common than Odets — both were creative, stubborn, and each was often characterized as “temperamental” by studios that were in the business of trying to crank out hits (particularly during the years of the Depression) and were not so much interested in whether a story had artistic merit.

After her affair with Odets soured Frances returned to her husband, Leif, in Los Angeles. The marriage began to crumble and talk of a divorce turned up in a few gossip columns by November 1939. In fact over the next couple of years the two were referred to in the newspapers as “ex” so often that I assumed they were divorced. Then I came across an item from the Los Angeles Times dated June 10, 1942 that stated that Erickson had just filed divorce papers in Reno so that he could marry actress Margaret Hayes.

Hotel Knickerbocker c. 1930s

Frances had spent the late 1930s and early 1940s earning a reputation for being difficult, primarily due to alcoholism. In mid-October 1942 Frances was arrested in Santa Monica for driving while intoxicated and for having bright headlights in a dimout area. She was fined $250, of which she paid a portion. She was given additional time to pay the balance. When she missed the deadline for payment a bench warrant was issued for her arrest. The actress was finally located at the Hollywood Knickerbocker where the arresting officers had to use a pass key to gain entrance to her room. Frances wouldn’t leave without a fight and she had to be forcibly dressed and dragged out of the building. All the while she was shouting “Have you ever had a broken heart?”

Frances would first be diagnosed with manic depressive psychosis, and soon thereafter with paranoid schizophrenia for which she would receive insulin shock therapy (later discredited as a treatment method).

Over the next several years Frances would spend much of her time as a patient at the Western State Hospital in Washington. Frances’ autobiography “Will There Really Be A Morning?” describes her incarceration at the hospital as a brutal nightmare. I don’t know if it was intentional or not, but in Quentin Tarantino’s film “Kill Bill” the bride (Uma Thurman) awakens from a coma in a hospital to discover that a sleazy orderly has been pimping her out. Similar outrages were alleged in Frances’ autobiography (which was probably entirely ghostwritten by a friend of hers). In the book it is said that she was a sex slave for some of the doctors and male orderlies. This unsubstantiated treatment of Frances was depicted in the 1982 film “Frances” starring Jessica Lange.

In 1978 Seattle film critic William Arnold published a fictionalized, and highly sensationalized, account of Frances’ life entitled “Shadowland”. The most salacious details of Frances’ life (many of which have been accepted as fact) seem to emanate from that book.

Frances at Television City c. 1958

One of the most horrendous “facts” of Frances’ life at Western State Hospital was that she’d had a lobotomy. Transorbital lobotomies were performed at the hospital during Frances’ time there; however, there is no record that she was ever subjected to the procedure.

Frances did make a comeback of sorts as the host of a local talk show that aired in Indianapolis from 1958 to 1964. The show “Frances Farmer Presents” remained in the number one position for its time slot during the entire run.

Frances Farmer died at age 56 of esophageal cancer in 1970.