Sun 3 Jul, 2016

Miss Freedom

Comments (0) Filed under: Hair Net Packages, LOS ANGELES MAGAZINETags: 1940s, Greatest Generation, Rosie the Riveter

I bought this Miss Freedom hair net package in an online auction several years ago for $10, and it feels like an appropriate item to spotlight this holiday week. The package portrays a WWII-era woman at her glamorous and sophisticated best—coiffed in face framing curls and wearing a blue gown that’s aglow with spangles.

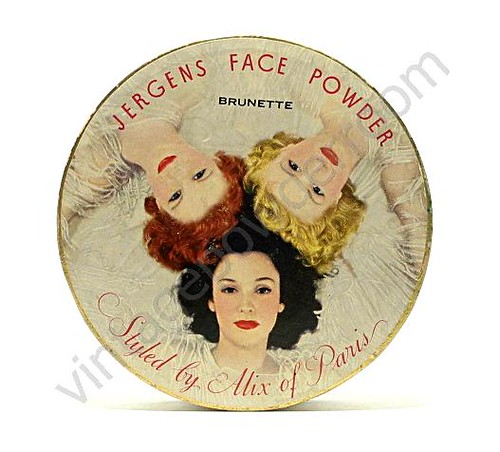

Despite wartime shortages and restrictions, women were exhorted during the 1940s to keep up their appearance as a way to boost the morale of their military mates and fellow factory workers. Headlines such as “Feminine Role in National Defense Starts at Beauty Shop” were typical, and hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles offered tips for maintaining a beauty routine while sticking to a budget that provided few funds for frills. After all, women didn’t put down their lipstick, face powder, or nail polish when they stepped in to fill gaps in the workforce, nor did they quit styling their hair.

My mom, Phyllis Renner

Many of the factories that employed female workers were savvy enough to understand the complex relationship between home front productivity and beauty rituals, so they installed onsite salons where a woman could get a manicure or a perm between shifts.

The Miss Freedom hair net package recalls for me the women of the Greatest Generation—especially my mother. My mom, Phyllis, worked for Cadillac in Detroit during WWII and she shared with me during my childhood stories of her wartime experiences, particularly how she and her friends scrimped and saved to buy the everyday beauty products we take for granted. My mom passed away over the Fourth of July weekend eight years ago, so the holiday is a melancholy time for me. This year when I think of her I will also mediate on the bravery and beauty of the women of her generation—and l will try to live up to the example they set.

While the women of the home front were keeping things on track, servicemen needed to be reminded why they were fighting, and what they were fighting for; and nothing sent a clearer message than a gorgeous pin-up picture.

While the women of the home front were keeping things on track, servicemen needed to be reminded why they were fighting, and what they were fighting for; and nothing sent a clearer message than a gorgeous pin-up picture.