Fri 30 Jan, 2009

DEAUVILLE

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: 1920s, Alexandre Dumas, Charles Dickens, consumption, Eleonora Duse, Franz Lizst, Greta Garbo, heroin chic, Lillian Gish, Marie Duplessis, prostitutes, Richard Hudnut, Sarah Bernhardt, Theda Bara, tuberculosis

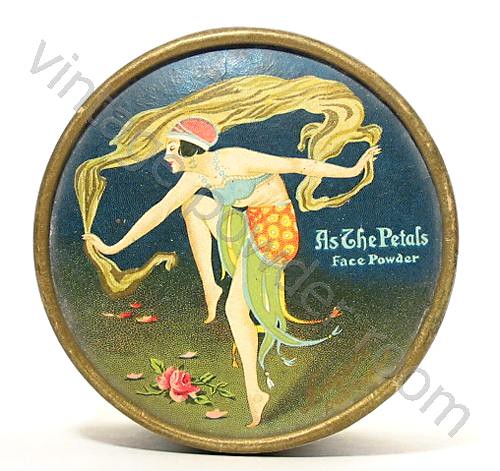

I love the image of the woman on the Richard Hudnut Deauville face powder box. I’ve always thought of her as a courtesan dressing for her paramour — she’s just the right combination of innocence and decadence. The face powder box dates from the early 1920s, but the image of the woman recalls an earlier time. While I love the blues and rock ‘n roll, I’m also a fan of opera, and to me the woman in the design represents the beautiful but doomed Violetta Valery from Verdi’s 1853 opera La Traviata. Verdi based his opera on the novel Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas (the younger — it was his father who wrote The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo).

Marie Duplessis

Dumas was born in Paris in 1824, and he was the illegitimate son of novelist Alexandre Dumas and dressmaker Marie-Laure-Catherine Labay. Dumas often tackled complex moral issues in his writings , such as the life of his fictional courtesan Marguerite Gautier. Dumas didn’t have to rely solely on his imagination to tell the story of Marguerite because she was a thinly veiled depiction of Dumas’ former lover Marie Duplessis.

Alexandre and Marie had a relationship that lasted only one year, and their affair was an open secret in Paris. It wasn’t until after Marie’s untimely death that Dumas began to write the story of the lady of the camellias. Dumas was typical of the time in which he lived, he seemed to have no qualms about taking a mistress, nor about appropriating her life story for his fiction, yet he would write frequently about the evils of prostitution. In fact, Dumas went so far as to propose to the government that all street prostitutes be deported to the colonies — out of sight, out of mind. Not exactly an enlightened approach to public policy and social ills.

Marie’s life story was much different than Dumas’ romanticized version. She was born Rose Alphonsine Plessis in Normandy, France in 1824. Marie’s parents weren’t a good match, and when they split up Marie’s mother abandoned her own family and became employed as the maid to an English family living in France. Marie was left in the care of her father, who shipped her out to the boonies to live with relatives. She lost her virginity at age 12 to a farm hand, and by 13 she’d been returned to her father who began to pimp her out. Despite her earning potential Marie’s father shipped her off again, this time she went to stay with relatives in Paris who owned a grocery. She worked as a clerk in a hat shop and saved enough money to get her own apartment in the Latin Quarter. Because she was vivacious and pretty she soon came to the attention of wealthy men who could buy her a better life than she could afford on her own.

Her first benefactor lasted only as long as his money held out. Marie’s subsequent lovers were wealthier and more powerful in turn, and she was finally able to move out of the Quarter and into a sumptuous apartment on Boulevard de Madelaine. If spending money was an Olympic event, Marie would have won multiple gold medals. She easily spent 100,000 francs per year on her personal upkeep, not including her staff. By the age of 20 she may have been the queen of the demi-monde in Paris — but she was also dying. Marie had consumption (tuberculosis) and it was destroying her. She knew she didn’t have long to live, and that knowledge, coupled with her deprived upbringing, undoubtedly fueled her compulsive spending and gambling habits.

Heroin Chic redux? An ad from c. 2007

Consumption has been common throughout human history. Ironically, during Marie’s lifetime women emulated the visible symptoms of the disease for fashion! People believed that the symptoms of the disease enhanced senstive, artistic dispositions. It was a kind of “TB chic” (just as the so-called “heroin chic” would have its day in the mid-1990s). The white skin, flushed cheeks, and luminous eyes were frequently achieved by using extremely dangerous substances. Among the potions used were compounds containing lead (many women died as a result of lead poisoning) and belladonna. Belladonna (the juice of the poisonous nightshade plant) was used to make a woman’s eyes bright as if she had a fever.

Greta Garbo in Camille

Marlene Dietrich may have presented a tragically romantic vision as she died in Robert Taylor’s arms in the 1936 film version of Camille (one of the many films based upon La Dame aux Camellias) but Marie’s end was excruciating. Shortly before she died she had met and fallen in love with the composer Franz Liszt. The love may have been reciprocated, but Lizst didn’t take Marie on tour with him. This would have been the time when so-called Listzomania was sweeping Europe, so perhaps he thought better of taking a lover on a tour during which women fought over shreds of his hankies and gloves. Lizst left on tour, and soon afterwards Marie spent her last days in agony before death released her.

Theda Bara

Marie was deeply in debt when she died, and her belongings were sold at auction — even her pet parrot! The auction drew crowds of people who were mostly interested in the vicarious thrill they could derive by handling the possessions of an infamous courtesan.

Among those in the crowd at the auction was author Charles Dickens. Of the crowd he said: “One could have believed that Marie was Jeanne d’Arc or some other national heroine, so profound was the general sadness.”

Marie’s life was brief, but she achieved immortality through Dumas’ work. Her story has been told many times in film and on stage, and she has been portrayed by actresses such as: Greta Garbo, Eleonora Duse, Lillian Gish, Theda Bara, and Sarah Bernhardt.

Marie’s funeral was reported to have been extravagant — drawing a crowd of hundreds. She is interred in Montmarte Cemetery.

On September 14, 1927, Isadora wrapped a long hand painted silk scarf around her neck and got into a car with Italian mechanic, Benoît Falchetto. As the car pulled away Isadora waved to a group of friends, reportedly saying “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire!” (“Goodbye, my friends, I am off to glory!”). The scarf fluttered dramatically behind her, but as the car picked up speed it became entangled in the spokes of one of the wheels and tightened around Isadora’s neck. The dancer was yanked out of her seat and over the rear of the car, and then dragged along the cobblestone street to her death.

On September 14, 1927, Isadora wrapped a long hand painted silk scarf around her neck and got into a car with Italian mechanic, Benoît Falchetto. As the car pulled away Isadora waved to a group of friends, reportedly saying “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire!” (“Goodbye, my friends, I am off to glory!”). The scarf fluttered dramatically behind her, but as the car picked up speed it became entangled in the spokes of one of the wheels and tightened around Isadora’s neck. The dancer was yanked out of her seat and over the rear of the car, and then dragged along the cobblestone street to her death.