Tue 12 May, 2009

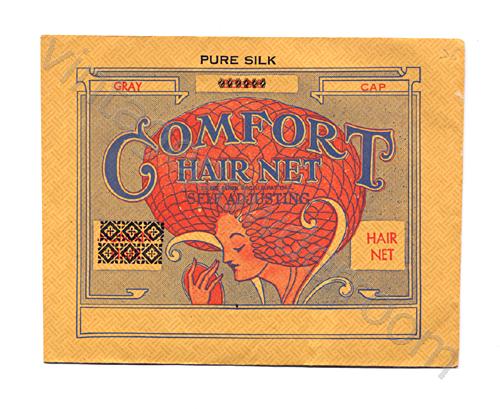

COMFORT HAIR NET

Comments (0) Filed under: Hair Net PackagesTags: Alphonse Mucha, Art Nouveau, Aubrey Beardsley, Cismonda, Gustav Klimt, James Dean, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Louise Abbema, Marlyn Monroe, Prince of Wales, psychedelic, Sarah Bernhardt, Shunga

The illustration on the Comfort Hair Net package reminds me of psychedelic rock ‘n roll posters from the 1960s. The ubiquitous posters advertised concerts that were held in every venue from the Fillmore West to the Fillmore East, and every dive bar in between. Organic, sensual, and other worldly, the style of the posters owed a huge debt to artists such as Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt, and Louis Comfort Tiffany. Is the name of the hair net a discreet nod to Tiffany? It’s unlikely, but not out of the question. Fixing a date for the hair net package is tricky, but because Art Nouveau was at its peak of popularity between 1890 and 1905 it is probably from that period.

Psychedelic art shared a similar aesthetic with its predecessor. Both styles are considered to be applied art (i.e., graphic design, fashion design, interior design, etc.) and both were in some sense lifestyles – at least their artifacts could be incorporated into one’s daily life. Art Nouveau was present in architecture, as well as in personal items such as jewelry. Psychedelic art encompassed music, light shows, fashion and interior design and was also a way in which to describe the experience of taking certain mind altering drugs like LSD or mescaline.

Psychedelic art shared a similar aesthetic with its predecessor. Both styles are considered to be applied art (i.e., graphic design, fashion design, interior design, etc.) and both were in some sense lifestyles – at least their artifacts could be incorporated into one’s daily life. Art Nouveau was present in architecture, as well as in personal items such as jewelry. Psychedelic art encompassed music, light shows, fashion and interior design and was also a way in which to describe the experience of taking certain mind altering drugs like LSD or mescaline.

The most controversial artist of the Art Nouveau period was Aubrey Beardsley. Beardsley’s subject matter was often erotic in nature and grotesque in execution – occasionally depicting enormous genitalia. He was quoted as saying “I have one aim—the grotesque. If I am not grotesque I am nothing.” He was influenced to some extent by Japanese Shunga, which is erotic art. One of the most beautiful and disturbing of the Shunga images is “Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife” by Katsushika Hokusai (c. 1820).

Alphonse Mucha was another artist who worked in the Art Nouveau style (sometimes even referred to as the Mucha style); and it was his work that was often cited as a major influence by the psychedelic artists of the 1960s. One of Mucha’s best known works is a poster that he did for the actress Sarah Bernhardt (“The Divine Sarah”) advertising her appearance as “Cismonda” in Paris. Sarah adored the poster, and it wasn’t that last one that Mucha would create for her.

Even though it was Mucha who produced posters of the “Divine Sarah”, she may have had more in common with Aubrey Beardsley. Both of them were extreme personalities, flamboyant and eccentric. Beardsley expressed himself quite often by donning outlandish garments, and Bernhardt frequently slept in a coffin so that she could “better understand my tragic roles”.

Even though it was Mucha who produced posters of the “Divine Sarah”, she may have had more in common with Aubrey Beardsley. Both of them were extreme personalities, flamboyant and eccentric. Beardsley expressed himself quite often by donning outlandish garments, and Bernhardt frequently slept in a coffin so that she could “better understand my tragic roles”.

Louise Abbema

During a performance of “Tosca” in Rio de Janeiro in 1905, Sarah injured her knee in a leap from a high wall. The leg never properly healed, and by 1915 gangrene had set in and the leg was amputated. It is said that she turned down $10,000 offered to her by a showman (not P.T. Barnum, who was long dead by 1915) for her amputated limb. Despite the loss of her leg Sarah Bernhardt continued to perform, as well as to run her own repertory company, until her death of uremia on March 23, 1923.