Fri 3 Jun, 2016

Nupical Face Powder Box

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder Boxes, LOS ANGELES MAGAZINETags: 1930s, Creola McCarter Milner, Gin Marriage

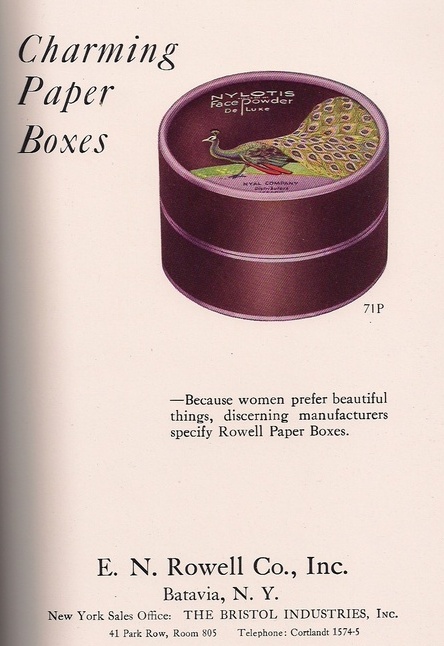

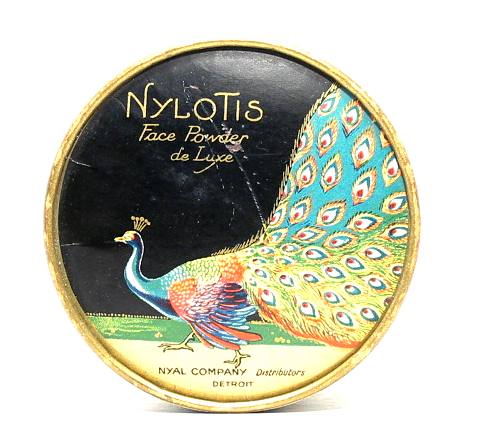

I found this Nupcial Face Powder box (c. 1920s) in a booth at an Orange County antique mall several years ago. I paid $30 for it. I’d never seen the brand before and expected never to see it again, but I was wrong. Earlier this week I discovered four Nupcial product labels for sale at an online auction site. I happily spent $95 for the labels in various sizes and shapes—they will look absolutely splendid framed.

What interests me about the powder box is its unusual mash-up of styles. Here, brightly colored geometric shapes, the hallmarks of Art Deco style, surround a classic 1920s bride. But while the graphics are era appropriate, they seem jarring. Brightly colored spears are attacking the poor woman!

The peculiar design of the Nupcial box sends a mixed message. Was the product meant to appeal to a traditional bride or to someone more fashion forward? The effect symbolizes the social chaos that characterized the Jazz Age, probably unintentionally so.

Apparently the widespread fear of moral decay that resulted in Prohibition led California legislators to pass a “gin marriage” law in 1927. The law was well meaning—it mandated a three day waiting period to discourage couples from drinking in speakeasies then making a mad dash for a local preacher to unite them in matrimony while three sheets to the wind.

Enacting a law may seem like a drastic step, but concerns about inebriated brides and grooms weren’t entirely unfounded. On December 19, 1930, the Los Angeles Times reported the story of a failed gin marriage. A pretty blonde stenographer, Creola McCarter Milner, sought an annulment from her husband of a few months. Creola told the judge that she had become intoxicated on the eve of her marriage and awakened four days later to find herself married to someone other than her intended.

Many women’s and religious groups believed that the law would lead to more and better marriages. Instead, it drove couples out of state to places like Yuma, Arizona and Las Vegas, Nevada where they could marry on a whim; the marriage rate in California declined precipitously and the divorce rate increased. Legislators came their senses and repealed the gin marriage law in 1943.

Upon second reflection, I think the graphics on the Nupcial face powder box conveys a decipherable message after all. The design may be a jumble of traditional and trendy, but it works in its own quirky way. I think the same can be said of marriage. My husband and I are a mixed bag of idiosyncrasies, yet our marriage thrives. And before you ask, we were sober when we exchanged our vows.