Mon 31 May, 2010

NO-TAIR HAIR NET

Comments (0) Filed under: Hair Net PackagesTags: 1920s, 1930s, Bonita Granville, Diana Rigg, Duesenberg, Emma Roberts, Esotouric, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Los Angeles Police Historical Society, Mildred Wirt Benson, Mrs. Emma Peel, Myrna Loy, Nancy Drew, Ruth Fielding, Ruther Bader Ginsberg, Sonia Sotomayor, The Avengers, Thin Man

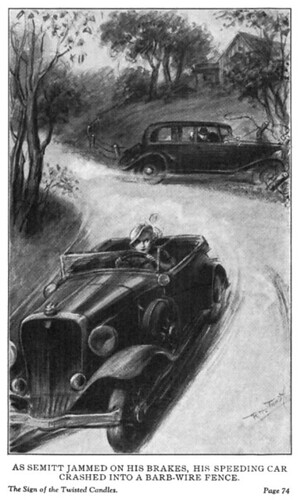

As soon as I saw the roadster (a Duesenberg?) in the illustration on the hair net package, I knew that the jaunty young lady at the wheel had to be the world renowned girl detective Nancy Drew.

When you were a child did you ever want to be Nancy Drew? I did. And all these years later I’m still so captivated by the idea of being a gal gumshoe, a dame detective, a she shamus, that I give crime tours with the LA-based company Esotouric on most weekends. But even the tours aren’t enough to satisfy my longing be a PI, cop, or a stylish and witty helpmate, like Myrna Loy in the Thin Man films.

Just because I never became a private investigator or cop (I like to believe that I DID become a stylish and witty helpmate) that doesn’t mean that I can’t pursue my crime busting dreams. I’ve discovered a few ways in which to get my crime fix — the aforementioned tours, and I volunteer at the Los Angeles Police Historical Society (LAPHS).

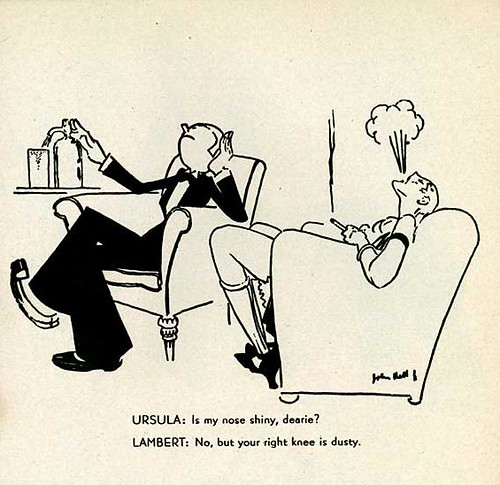

Diana Rigg as Mrs. Peel

The historical society has a fantastic museum which is housed in an old police station. I spend my time there organizing and digitizing a collection of Daily Bulletins, and Juvenile Reports. The Bulletins began in 1907 and were distributed to each officer, every day (with the exception of Sundays and holidays). The Bulletins provide a daily snapshot of life in the growing city of Los Angeles, as reflected in the criminal behavior of its citizens.

Nancy Drew did her sleuthing in River Heights, not in Los Angeles, and she began her amateur detecting as a 16 year old in 1930. The early books depict Nancy as a very modern girl — just as she should have been in the years following WWI. She had a litany of accomplishments including: dancer, driver, cook, car mechanic, swimmer, seamstress, painter — and she was fluent in French! If she’d had a leather cat suit, I’m sure she could have given Mrs. Emma Peel (of the 1960s series The Avengers) a run for her money.

Mildred in mid-dive c. 1925

The woman who ghosted the Nancy Drew books for the Stratemeyer Syndicate from 1929 to 1953 was Iowan, Mildred Wirt Benson. Mildred was nearly as accomplished as Nancy. At the University of Iowa she participated in swimming, soccer, and was a student journalist. Following graduation she worked as a general reporter for the The Clinton (Iowa) Herald.

Mildred was only 21 when, in 1926, she answered an ad placed by the Stratemeyer Syndicate for ghost writers. Her first assignment resulted in the novel, Ruth Fielding and Her Great Scenario.

Mildred appears to have remained as feisty as Nancy Drew ever was, because she began to take flying lessons at age 59. I’m glad to report that Mildred lived a long life – she passed away in 2002 at the age of 96.

Nancy Drew has gone on to have a long and eventful life too. There were some terrific films in the 1940s featuring Bonita Granville as Nancy, and more recently (2007) Emma Roberts played the girl sleuth. In 2002 the first Nancy Drew book, The Mystery of the Old Clock, sold over 150,000 copies!

Oh, and if you think that Nancy Drew was a pre-feminist bimbo who couldn’t possibly have had an impact on intelligent and strong women, think again. Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton cites her as an early influence, and so do Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and Sonia Sotomayor.

For more information on Mildred Wirt Benson visit the University of Iowa Digital Library.