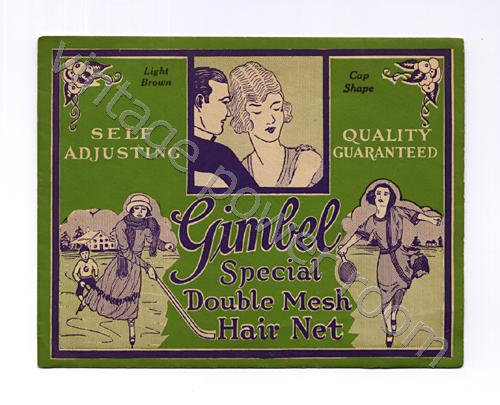

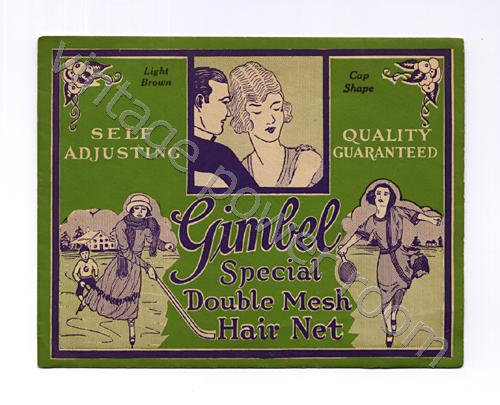

The Gimbel hair net envelope dates from the early to mid 1920s. The sweet little floral design in the upper corners is typical of the period, and the depiction of women playing sports reflects the sports mania that was a large part of the era.

I have an admission to make — I did not give up a promising career in sports to become a writer. Things may have been different for me if I’d been around in the 1920s because sports of all kinds were wildly popular. In particular, women enthusiastically participated in everything from tennis to hockey. Maybe I’d have found my sport and excelled in it, just like Suzanne Lenglen did.

Suzanne Rachel Flore Lenglen was born on May 24, 1899 about 70 km north of Paris, France, and she would become the first female superstar in tennis, and also the first major tennis star to turn professional. Suzanne was a sickly child who suffered from several ailments, including chronic asthma, so her father suggested that she try tennis as a way to build her strength. Almost immediately she demonstrated a talent for the sport and her father began to train her in earnest. He would place handkerchiefs around the court which he would then expect Suzanne to be able to hit with a serve or return. Young Suzanne was an apt pupil and she quickly became a player to be reckoned with.

In 1914, only four years after beginning to play, Suzanne spent her 15th birthday winning the World Hard Court Championship at Saint-Cloud. The outbreak of World War I at the end of 1914 put an end to most national and international tennis competitions, and Lenglen would have to wait until 1920 to begin to compete on the world stage.

King George and Queen Mary

At Wimbledon in 1920 the young French woman faced Dorthea Douglass Chambers. Chambers had won at Wimbledon seven times previously, and Suzanne had never before played on a grass court! The women played to a packed stadium of several thousand spectators, including King George V and Queen Mary!

Charlotte Cooper

Sure, it was a stellar match — which Suzanne went on to win, but what really captured the attention of the crowd was the audacity of Lenglen’s tennis costume, and maybe the fact that she would sip brandy from a flask between sets. In the years prior to 1920 women had played tennis dressed similarly to Charlotte Cooper, and probably sans a booze filled flask.

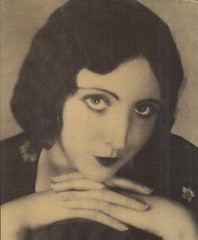

Suzanne was a rebel. She would play tennis in a dress that fell only to mid-calf (revealing the tops of her stockings when she moved just so); and if that wasn’t shocking enough, she bared her forearms, wore a nifty little bandeau, often secured with a brooch, on her cropped ‘do and she frequently appeared on the court in make-up. She was given the nickname La Divine and it suited her. She was a sports diva. She was passionate and wasn’t shy about showing her emotions. She would often pout or burst into tears if she played badly.

Suzanne Lenglen

Imagine for a moment being dressed like Charlotte Cooper and then attempting to compete with Suzanne as she darted around the court unencumbered by a voluminous skirt, long sleeves, starched collar and tie!

Jean Patou

Suzanne’s daring costume revolutionized the way in which women dressed to play tennis, and in addition to her cutting edge tennis togs(designed by the legendary couturier Jean Patou!), Suzanne made a fashion statement off of the court with her bobbed hair, make-up, and clothing in the latest styles. She was admired for her skill with a tennis racket, and for her fashion sense. In fact, Miss Lenglen even had a tennis shoe named after her!

Suzanne at Wimbledon, 1926

So, let’s raise a flask of brandy (or in my case a gin gimlet) and make a toast to the incomparable Suzanne Lenglen. What a remarkable woman. She won at both Wimbledon and the French Open setting records that would remain unbroken for decades.

Suzanne would retire from the world of tennis and go on to found a school where she would teach others to play and to love the game. Among her accomplishments she was an author who wrote Lawn Tennis (1925), Lawn Tennis for Girls (1930), and Tennis by Simple Exercises (1937).

Tragically, her life would be cut short. She was diagnosed with leukemia in June of 1938. Three weeks following a newspaper report of her ailment she went blind. She died at age 39 on July 4, 1938 of pernicious anemia.

Tragically, her life would be cut short. She was diagnosed with leukemia in June of 1938. Three weeks following a newspaper report of her ailment she went blind. She died at age 39 on July 4, 1938 of pernicious anemia.

Suzanne’s legacy lives on — Court Suzanne Lenglen is the secondary tennis court at the Stade Roland Garros in Paris, France. It was built in 1994 and holds 10,068 spectators. There is a statue of Suzanne, in full stride, outside of the stadium.

Tragically, her life would be cut short. She was diagnosed with leukemia in June of 1938. Three weeks following a newspaper report of her ailment she went blind. She died at age 39 on July 4, 1938 of pernicious anemia.

Tragically, her life would be cut short. She was diagnosed with leukemia in June of 1938. Three weeks following a newspaper report of her ailment she went blind. She died at age 39 on July 4, 1938 of pernicious anemia.