Thu 25 Sep, 2008

DUSKA

Comments (1) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: Anais Nin, Art Deco, Ernest Hemmingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, gin, Henry Miller, John Dos Passos, Josephine Baker, Lalique, moderne, Paris, WWI

Duska Face Powder Box c. 1925

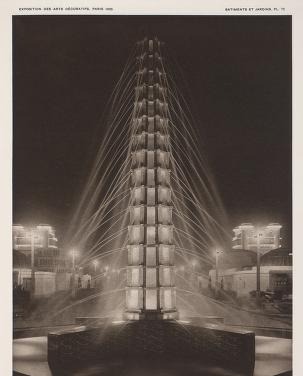

The face powder box shown above is called Duska. You can tell that the box was created during the 1920s because the fountain design was borrowed from Rene Lalique’s crystal fountain, which had been a feature at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris during 1925. It was the exposition that introduced the moderne style, later dubbed art deco, to the world.

Lalique Fountain

Lalique’s fountain had a structure reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower, but the water flowed out in way that gave it soft undulating curves, much like those of the Paris Metro signs.

The expo had originally been expected to open in 1914 – but WWI intervened. It wasn’t until 1921 that the financing and location were settled, and the expo finally opened in 1925.

The moderne style grew out of several styles, including art nouveau. While art nouveau reveled in sensuous curves and muted tones, the moderne style was vibrant in color, and its shapes were geometric.

The design of the Duska face powder box borrows elements from both Art Noveau and Art Deco.

Josephine Baker

If I could time travel, I’d like to spend a while as an expatriate in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s. Following WWI, the “War to End All Wars”, Paris was inhabited by artists, writers, and some of the physical and emotional causalities of the horrors of trench warfare.

Many of the people who came of age during the years following WWI rejected 19th century values, and its art, and earned the moniker the “Lost Generation“. Some of the Americans who gravitated to the expat’s life in Paris would become international literary superstars: Ernest Hemmingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos. Others of them were artists and performers, like Josephine Baker.

I visualize myself at a sidewalk café (where else?) watching the passing parade of literati. Maybe I’d be involved in a steamy assignation a la Anais Nin and Henry Miller.

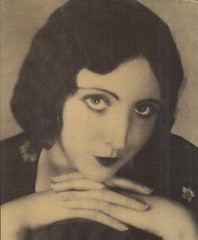

Anais Nin

It would have been an exciting place to be, with a cast of characters one can only dream about. Fortunately, there are ways in which to vicariously experience life in Paris during the 1920s/30s – you can read Hemmingway’s novels, Anais Nin’s diaries or erotica, Henry Miller’s novel “Quiet Days in Clichy” (which I loved) or rent the 1988 film “The Moderns” or the 1990 film “Henry and June” , which was based upon a portion of Nin’s diaries.

Until time travel becomes an option, we’ll have to use our imaginations – so mix yourself a gimlet (gin, please!), slip into vintage clothes, and curl up with one of the aforementioned books, watch one of the movies, or listen to le jazz hot.

And ladies – don’t forget to powder your nose.