Sun 5 Feb, 2017

Max Factor Lipstick Ad

Comments (0) Filed under: Advertisements, Lipstick, LOS ANGELES MAGAZINETags: Butterfield 8, Elizabeth Taylor, John Garfield, Lana Turner, Max Factor, The Postman Always Rings Twice

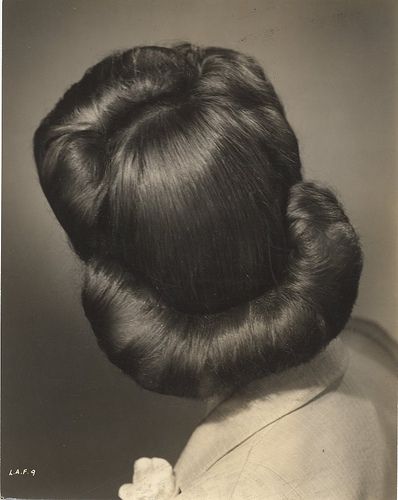

A redheaded Lana Turner advertises Max Factor lipstick and her role in the MGM film “Cass Timberlane”

Lipstick has been around for centuries. The women of ancient Mesopotamia crushed gemstones and applied them to their lips, and Egyptian women colored their lips using crushed carmine beetles. But arguably the most important lipstick innovation was made by Max Factor when, in 1930, he created lip gloss.

Factor began his incredible career by creating makeup specifically for film, so it is not surprising that many of his ads featured Hollywood stars. The Max Factor ads were frequently a clever cross promotion highlighting not only the cosmetics, but a popular actress and her current project, too.

I know I am not alone in believing lipstick to be the perfect cosmetic; It is small enough to tuck into an evening bag and most women will not leave home without a tube of their current favorite color in their purse. Applying lipstick may have become second nature for those who wear it, but it is a uniquely feminine and extremely intimate act—perhaps that is one of the reasons people during the 1920s were scandalized when women first began to use it in public (this despite the beauty preferences of the women of ancient Mesopotamia).

I know I am not alone in believing lipstick to be the perfect cosmetic; It is small enough to tuck into an evening bag and most women will not leave home without a tube of their current favorite color in their purse. Applying lipstick may have become second nature for those who wear it, but it is a uniquely feminine and extremely intimate act—perhaps that is one of the reasons people during the 1920s were scandalized when women first began to use it in public (this despite the beauty preferences of the women of ancient Mesopotamia).

Then and now, a delicate pink lipstick was as sweet and innocent as a girl’s first kiss. In deep, luscious red it can be seductive, lustful and, quite frankly, a home wrecker. The wicked little cosmetic leaves tell-tale traces on clothing and skin, and it’s famous for lingering provocatively on a cigarette smoldering in an ashtray and smeared cocktail glasses. And it has other applications, too. Lipstick has been used to write love letters and ransom notes, and even to spark romantic connections in films. (Butterfield 8, in which Elizabeth Taylor used lipstick to scrawl NO SALE across a mirror—her message to a lover who thought he could possess her soul, and The Postman Always Rings Twice, in which a tube of rolling lipstick creates the sexual tension between John Garfield and Lana Turner come to mind.)