Wed 31 Oct, 2012

ADORATION

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: 1920s, 1930s, Dia de los Muertos, Elijah Bond, Halloween, Ouiji board, Patience Worth, Pearl Curran, Sherlock Holmes, Timothy O'Sullivan, WWI

The Adoration Face Powder box dates from the 1920s/1930s, and because the design on the box appears to be that of a spider web it brings to my mind the spooky goings on of Halloween.

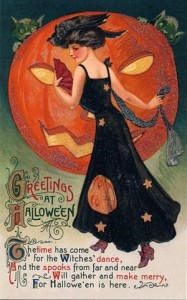

Halloween is a contraction of “All Hallows’ Eve” and it is an annual celebration observed in many countries on October 31, the eve of the feast of All Hallows (or All Saints).

Scholars believe that the celebration was originally influenced by western European harvest festivals and festivals of the dead. The end of the harvest season is a symbolic death — the fields are left fallow for a period of time in order to restore their fertility — to be resurrected in the spring.

In A HARVEST OF DEATH, Civil War photographer Timothy H. O’Sullivan captured the image of dead soldiers on a battle field waiting to be collected, or harvested, for burial.

The dead have a powerful hold on the living, and festivals of the dead have been observed in many different cultures for centuries.

One of the best known festivals of the dead is Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Dia de los Muertos is a Mexican holiday and is held on November 1st (honoring deceased children) and November 2nd (honoring deceased adults). The living go to cemeteries to be with the souls of the departed. Private altars are built at grave sites and may contain favorite foods, beverages, photos, and other memorabilia of the departed.

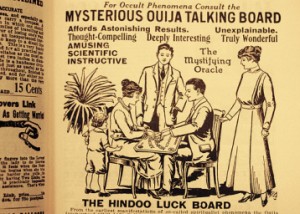

Spending quality time with the souls of the departed wasn’t enough for the Victorians, they wanted to speak with their deceased loved ones. Elijah Bond, an American lawyer and inventor, made chatting with the deceased a reality — well, if you believe in the power of the Ouija board. On July 1, 1890 the Ouija board was introduced by Bond, and he received a patent for it in 1891.

The Ouija board was originally regarded as a harmless parlor game; but following the carnage of WWI many people were desperate to reach loved ones who had been killed during the conflict, and they searched for ways in which to communicate with their sons, brothers, and husbands. Many of the survivors of the Great War, including the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, found comfort in spiritualism.

The Ouija board was originally regarded as a harmless parlor game; but following the carnage of WWI many people were desperate to reach loved ones who had been killed during the conflict, and they searched for ways in which to communicate with their sons, brothers, and husbands. Many of the survivors of the Great War, including the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, found comfort in spiritualism.

Pearl Curran was an American spiritualist who popularized the Ouija board as a divining tool. By all accounts she was an ordinary girl with no special gifts or particular ambitions. She married John Howard Curran when she was 24. The couple’s upper middle-class lifestyle afforded Pearl the opportunity to spend her free time playing cards and calling on friends.

In 1912 Pearl and her friend Emily Grant Hutchings paid a call on a neighbor who had a Ouija board. During the visit Emily claimed to have received a message from a relative. Emily purchased a Ouija board and took it to Pearl’s house with the plan of communicating further with the spirit of her deceased relative.

Initially Pearl was indifferent to her friend’s new obsession, but she finally agreed to participate at the board. On June 22, 1912 Pearl received a communication from a spirit who identified herself as only as Pat-C. Then on July 18, 1913 the board became possessed with unusual strength and energy and Pat-C began to reveal further information about herself. She said “Many moons ago I lived. Again I come. Patience Worth my name. Wait, I would speak with thee. If thou live, then so shall I.”

In 1916, Pearl Curran wrote a book publicizing her claims that she had contacted the long dead Patience Worth. By 1919 the pointer on Pearl’s board would just move around aimlessly, but it didn’t matter. Pearl had progressed to pictorial visions of Patience Worth. She said “I am like a child with a magic picture book. Once I look upon it, all I have to do is to watch its pages open before me, and revel in their beauty and variety and novelty…”

In 1916, Pearl Curran wrote a book publicizing her claims that she had contacted the long dead Patience Worth. By 1919 the pointer on Pearl’s board would just move around aimlessly, but it didn’t matter. Pearl had progressed to pictorial visions of Patience Worth. She said “I am like a child with a magic picture book. Once I look upon it, all I have to do is to watch its pages open before me, and revel in their beauty and variety and novelty…”

Pearl became Patience’s amanuensis, and she faithfully transcribed the stories that came to her through Worth’s spirit. Together the pair wrote novels including: Telka; The Sorry Tale; Hope Trueblood; An Elizabethean Mask as well as several short stories and many poems.

Of course there were the inevitable naysayers who didn’t buy Pearl’s story of a long dead writing partner. Some of the skeptics noted that Patience was somehow able to write a novel about the Victorian age, which came 200 years after she had lived.

However it happened, the literature produced by Patience Worth was considered by many to be first rate. Worth was cited by William Stanley Braithwaite in the 1918 edition of the Anthology of Magazine Verse and Year Book of American Poetry by printing the complete text of five of her poems, along with other leading poets of the day including William Rose Benet, Amy Lowell, and Edgar Lee Masters!

Here is one of Patience Worth’s poems, The Deceiver:

I know you, you shamster! I saw you smirking, grinning

Nodding through the day, and I knew you lied.

With mincing steps you gaited before men, shouting of your valor,

Yet you, you idiot, I knew you were lying!

And your hand shook and your knees were shaking.

I know you, you shamster! I heard you honeying your words,

Licking your lips and smacking o’er them, twiddling your thumbs

In ecstasy over your latest wit.

I know you, you shamster!

You are the me the world knows.

Pearl Curran’s husband, John, passed away on June 1, 1922. It was John who had kept meticulous records of the Patience Worth sessions, so with his death the records became sporadic and fragmentary.

Pearl married two more times but the marriages were short-lived. In the summer of 1930 Pearl left her home in St. Louis for good and moved to California to live with an old friend in the Los Angeles area. On November 25, 1937 Patience communicated for the last time; she said that Pearl was going to die very soon.

Even though Pearl had not been in ill health, she developed pneumonia in late November and passed away on December 3, 1937.

Even though Pearl had not been in ill health, she developed pneumonia in late November and passed away on December 3, 1937.

A thorough investigation of the Pearl/Patience case was conducted during Pearl’s lifetime by Dr. Franklin Prince. In 1927 the Boston Society for Psychic Research published Dr. Prince’s book. As a part of his investigation Dr. Prince wrote an article entitled The Riddle of Patience Worth, which appeared in the July 1926 issue of Scientific American. He asked that anyone with information on the Pearl/Patience case to contact him, but no one ever did.

If you’d like to learn more about Pearl Curran and Patience Worth, visit the website dedicated to her (them?)

HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

Tragically, her life would be cut short. She was diagnosed with leukemia in June of 1938. Three weeks following a newspaper report of her ailment she went blind. She died at age 39 on July 4, 1938 of pernicious anemia.

Tragically, her life would be cut short. She was diagnosed with leukemia in June of 1938. Three weeks following a newspaper report of her ailment she went blind. She died at age 39 on July 4, 1938 of pernicious anemia.