Sun 22 Jan, 2017

Holdfast Hair Pins

Comments (0) Filed under: Hair Pins, LOS ANGELES MAGAZINETags: 1920s, bobbed hair, flappers, Holdfast Hair Pins, Luis Marco, Robert "Bobby" Pinsworth

The vibrant colors and Art Deco design of this Holdfast Hair Pin card didn’t catch my eye until I saw it listed in an online auction. The woman’s bobbed hair is typical of the flapper era, and it was easy for me to envision her in a short dress and rolled stockings, stopping by her local five-and-dime to pick up a card of Holdfast hair pins to keep her newly shorn locks in place.

I can’t conceive of life without bobby pins, and it is my contention that they are the unsung heroines of a woman’s beauty tool kit. I wear my hair short, so I don’t often use them, but I keep a few stashed in my bag anyway. A recent purse search turned up my wallet, cell phone, a handful of loose change, a lipstick I had been searching for since last week, and three bobby pins.

The spare change may come in handy, and I’m glad the lipstick finally turned up, but I tossed the bobby pins right back into my purse because I find the ingenious metal clips are as useful—or even more useful than—any multi-purpose knife. They can be used to create a halo of face framing curls or as an improvised paper clip, bookmark, screwdriver, fishhook, cherry pitter, or lock pick. Unconvinced of the bobby pin’s superiority? Just try holding your hair in place with any of the objects listed above.

Given their usefulness, it is no wonder that at least half a dozen people have sought to take credit for the bobby pin’s invention. First was an imaginative 15th century fellow, the eponymous Robert “Bobby” Pinsworth. According to some sources, Mrs. Pinsworth was having a bad hair day when she asked her husband for something to hold an errant strand in place. Bobby came through with a uniquely designed clip that changed Mrs. P’s life.

In March 1990, Luis Marco, a 1920s San Francisco cosmetics manufacturer was eulogized in a local newspaper as the originator of the bobby pin. His daughter said that he had toyed with the idea of naming it the Marcus Pin, but named it after bobbed hair instead.

The only historical consensus about the humble little clip seems to be that it was created during the Roaring 20s, like the Holdfast Hair Pins, for flappers coping with their newly cropped dos; but whether the clever ribbed metal device was the brainchild of Bobby Pinsworth, Luis Marco, or someone else altogether, its true creator remains a beautiful mystery.

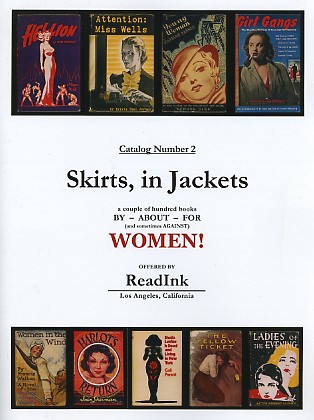

Oh, and the titles are simply amazing — “Ladies of the Evening”, “Women in the Wind”, “Yesterday’s Sin”.

Oh, and the titles are simply amazing — “Ladies of the Evening”, “Women in the Wind”, “Yesterday’s Sin”.