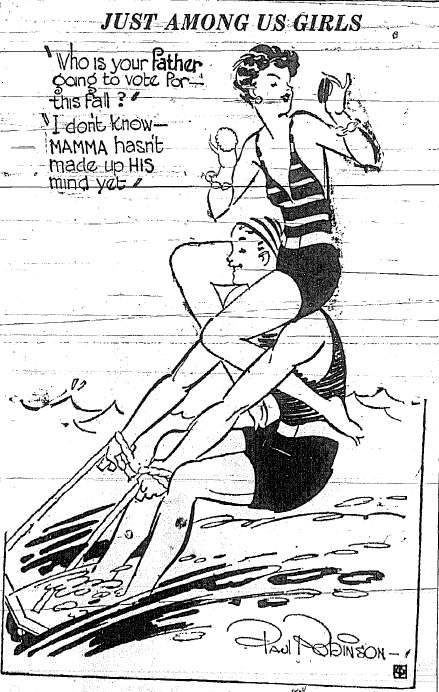

The design on the hairnet package above is emblematic of the 1920s in Southern California: surf, sand, sun and sin. What? You don’t see any sin in the design? I guess it’s just my evil mind — the first thing that I thought of was Sister Aimee Semple McPherson’s mysterious disappearance from Venice Beach on May 18, 1926. What did her disappearance have to do with sin? Read on.

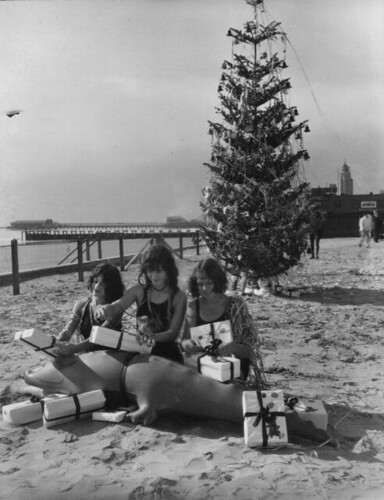

Southern California beaches weren’t just places from which to disappear in the 1920s — they were obviously places to relax (and to wear your prettiest bathing costume.) I was pleasantly surprised to discover a beautiful souvenir folder of Venice Beach which not only shows people enjoying a day at the beach, but echoes the design of the hairnet package. Note the similarities in the coloration and overall design — really quite nice.

Aimee was born Aimee Elizabeth Kennedy on October 9, 1890 on a farm in Canada. It was her mother, Mildred (Minnie), who first introduced young Aimee to religion. Minnie worked with the Salvation Army and her daughter would often accompany her to soup kitchens.

Click on photo to see Sister McPherson preach.

While other little girls may have preferred to play house with their dolls, Aimee played “Salvation Army” with hers. Sermonizing to a congregation of dolls may not have been particularly thrilling or rewarding, but it was good practice for her adult life.

Aimee and Robert Semple

Given her interest in religion and the fact that, even in high school, she was protesting the teaching of evolution in public schools, it’s no surprise that she fell for a Pentecostal missionary from Ireland, Robert James Semple.

She converted to her husband’s faith and they married on August 12, 1908. The newlyweds immediately took off on an evangelistic tour of Europe. Continuing their mission they arrived in Hong Kong, China in June 1910, where both contracted malaria. Robert died on August 19, 1910 and was buried in Hong Kong. Aimee was just beginning to recover from the same illness that took her husband when she gave birth to a daughter, Roberta Star Semple, on September 17, 1910.

Newly widowed and a recent mother, Aimee continued to convalesce in New York, and it was there that she met accountant Harold Stewart McPherson. They were married on May 5, 1912, and their son, Rolf, was born on March 23, 1913.

Aimee on the road

In mid-1915 Aimee took her act on the road and held tent revival meetings up and down the Eastern Seaboard, eventually heading out to other parts of the country. Whatever his reasons, Harold wasn’t always able to travel with his wife and their marriage suffered. In 1918 he filed a petition for divorce (citing abandonment) and the divorce was granted in 1921.

Aimee eventually tired of being on the road and settled in Los Angeles. Her ministry was so successful that she was able to build the Angelus Temple in Echo Park (dedicated in 1923).

Sister Aimee was at the zenith of her influence and popularity by 1926. And then it all began to unravel.

On May 18, 1926 McPherson went with her secretary to Ocean Park Beach, just north of Venice Beach, to swim. It was from there that Aimee vanished. Had she drowned? Her mother thought so. Aimee had been scheduled to preach later that day, but Minnie filled in. She ended her emotional sermon by telling the parishioners that “Sister is with Jesus”.

Mourners kept a seaside vigil for their beloved Aimee, but she did not emerge from the sea. Sadly, one parishioner drowned searching for McPherson, and a diver perished from exposure.

Mourners kept a seaside vigil for their beloved Aimee, but she did not emerge from the sea. Sadly, one parishioner drowned searching for McPherson, and a diver perished from exposure.

It didn’t take long for people to notice that Kenneth G. Ormiston, the engineer for Aimee’s radio station, KFSG, had disappeared as well. Some felt that Ormiston and McPherson had run off together — they had become very friendly.

A month passed when finally there was word of Aimee in the form of a ransom note delivered to her mother. The note demanded a half million dollars or else McPherson would be sold into “white slavery”. The note was signed “The Avengers”. Believing that her daughter was dead, Minnie tossed the letter.

On June 23rd, like a biblical prophet, Aimee staggered out of the desert into a Mexican town just across the border from Douglas, Arizona. Aimee’s story was that she’d been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held in a shack until she managed to escape, walking 13 hours to freedom.

On June 23rd, like a biblical prophet, Aimee staggered out of the desert into a Mexican town just across the border from Douglas, Arizona. Aimee’s story was that she’d been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held in a shack until she managed to escape, walking 13 hours to freedom.

There were several gaping holes in her story: her shoes were grass stained and showed no signs of a 13 hour desert trek and, furthermore, she’d disappeared from the beach clad only in a bathing suit, yet she had turned up following her abduction fully dressed and wearing her own wristwatch. To make matters worse, no sign of the shack where she was allegedly held was ever discovered. A grand jury convened on July 8, 1926, but they adjourned after 12 days saying they hadn’t enough evidence to proceed against the wandering minister. The Grand Jury reconvened when new evidence was uncovered. The evidence suggested that Aimee and Kenneth had been traveling together, and signing into motels along the way.

What had Aimee really been up to for over one month? Had she been kidnapped as she continued to maintain, or had she gone off to have an abortion, or heal from plastic surgery? We’ll probably never know. District Attorney Asa Keyes dropped all of the charges, thus ending any official investigation.

Despite the bad press she’d received Aimee continued her good works, but her reputation had been permanently damaged. Involved in a power struggle with her mother over control of the church, Aimee had a nervous breakdown in 1930.

David Hutton w/ballet dancers

McPherson would marry for a third time on September 13, 1931 to actor and musician David Hutton. Two days into the marriage the groom was sued for alienation of affection by Hazel St. Pierre. Hutton claimed never to have met Hazel, but she still managed to walk away with a settlement of $5,000. Things would get worse. Aimee was in Europe when she heard that Hutton was billing himself as “Aimee’s man” in his cabaret act. Let’s hope he wasn’t performing “The Ballad of Aimee McPherson”. David and Aimee were divorced on March 1, 1934.

On September 26, 1944 McPherson traveled to Oakland, California for a series of revivals. When her son went to her hotel room at 10 am the next morning to fetch her for her sermon, he found her unconscious. Aimee would die less than two hours later. The coroner was not able to conclusively determine the casue of death. Apparently Aimee had been taking sleeping pills (Seconal) and it is most likely that her death was the result of an accidental overdose.

On September 26, 1944 McPherson traveled to Oakland, California for a series of revivals. When her son went to her hotel room at 10 am the next morning to fetch her for her sermon, he found her unconscious. Aimee would die less than two hours later. The coroner was not able to conclusively determine the casue of death. Apparently Aimee had been taking sleeping pills (Seconal) and it is most likely that her death was the result of an accidental overdose.

I wonder if there was something in the air during 1926 that caused two very famous women to mysteriously vanish, and then to reappear without a credible explanation. The first woman was, of course, Aimee Semple McPherson — the second woman was famed mystery writer Agatha Christie!

On December 8, 1926 after being told by her husband Archie that he was in love with another woman and wanted a divorce, Agatha vanished. She’d left notes for both her husband and her secretary saying that she was going to Yorkshire. Her car was found abandoned and for a while it appeared that she’d been the victim of foul play.

About ten days later Agatha was identified as a guest at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel (now the Old Swan Hotel) in Harrogate. Agatha would never give a full account of her disappearance. Two doctors diagnosed her as suffering from amnesia. I believe it was the news of Archie’s infidelity that caused her to go off the rails for a while.

Max and Agatha

Archie and Agatha would divorce, and in 1930 she would marry an archaeologist Max Mallowan, whom she’d met on a dig in the Middle East. The Mallowans would have a long and happy marriage.

For a wonderful fictional account of how Agatha spent her missing days, watch the 1979 film “Agatha” starring Vanessa Redgrave and Dustin Hoffman.

Mourners kept a seaside vigil for their beloved Aimee, but she did not emerge from the sea. Sadly, one parishioner drowned searching for McPherson, and a diver perished from exposure.

Mourners kept a seaside vigil for their beloved Aimee, but she did not emerge from the sea. Sadly, one parishioner drowned searching for McPherson, and a diver perished from exposure. On June 23rd, like a biblical prophet, Aimee staggered out of the desert into a Mexican town just across the border from Douglas, Arizona. Aimee’s story was that she’d been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held in a shack until she managed to escape, walking 13 hours to freedom.

On June 23rd, like a biblical prophet, Aimee staggered out of the desert into a Mexican town just across the border from Douglas, Arizona. Aimee’s story was that she’d been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held in a shack until she managed to escape, walking 13 hours to freedom.

On September 26, 1944 McPherson traveled to Oakland, California for a series of revivals. When her son went to her hotel room at 10 am the next morning to fetch her for her sermon, he found her unconscious. Aimee would die less than two hours later. The coroner was not able to conclusively determine the casue of death. Apparently Aimee had been taking sleeping pills (Seconal) and it is most likely that her death was the result of an accidental overdose.

On September 26, 1944 McPherson traveled to Oakland, California for a series of revivals. When her son went to her hotel room at 10 am the next morning to fetch her for her sermon, he found her unconscious. Aimee would die less than two hours later. The coroner was not able to conclusively determine the casue of death. Apparently Aimee had been taking sleeping pills (Seconal) and it is most likely that her death was the result of an accidental overdose.

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

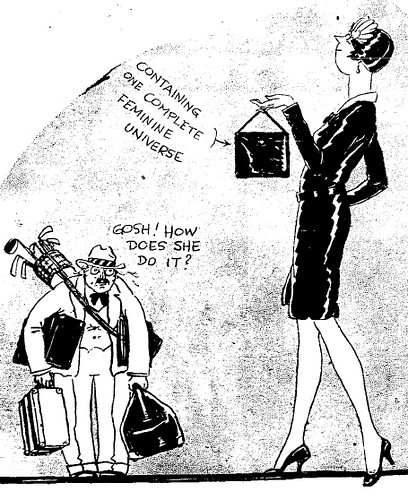

Twenty-four year old Gene Anderson was a lingerie designer , so she she took a particular interest in current fashion, and she loved to wear expensive clothes.

Twenty-four year old Gene Anderson was a lingerie designer , so she she took a particular interest in current fashion, and she loved to wear expensive clothes.

Upon being searched by a matron at the County Jail, it was discovered that Gene was packing a loaded revolver in her vanity bag!

Upon being searched by a matron at the County Jail, it was discovered that Gene was packing a loaded revolver in her vanity bag!