Sat 25 Jun, 2011

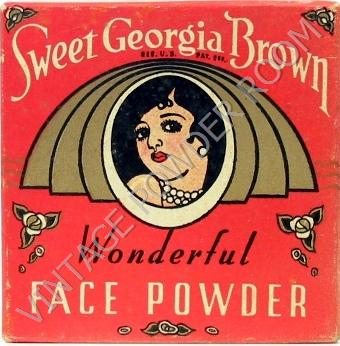

SWEET GEORGIA BROWN

Comments (1) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: belly dance, Bruno Koschmieder, Clara Bow, Columbian Exposition, Earl Snake Hips Tucker, Elvis Presley, Ethel Waters, Farida Mazar Spyropoulous, hoochee-coochee, J. Edgar Hoover, Little Egypt, Madame C.J. Walker, pomade, race records, The Beatles, Tony Sheridan

In previous posts I’ve discussed the creation and marketing of face powder for African American women. Among the pioneers in cosmetics for women of color was the brilliant business woman Madame C.J. Walker.

“Sweet Georgia Brown” face powder wasn’t one of Madame Walker’s products, but it was obviously intended for sale to what was then often referred to as the “race” market. Although in hindsight the term “race” in the context of marketing products may seem to be a derogatory one, in the early 20th century the African American press routinely used the term “the Race” to refer to African Americans as a whole, and used the terms “race man” or “race woman” to refer to African American individuals who showed pride and support for their people and culture. In other words, it was a different time.

“Sweet Georgia Brown” face powder wasn’t one of Madame Walker’s products, but it was obviously intended for sale to what was then often referred to as the “race” market. Although in hindsight the term “race” in the context of marketing products may seem to be a derogatory one, in the early 20th century the African American press routinely used the term “the Race” to refer to African Americans as a whole, and used the terms “race man” or “race woman” to refer to African American individuals who showed pride and support for their people and culture. In other words, it was a different time.

Among the women who may have used products such as “Sweet Georgia Brown” face powder was entertainer Ethel Waters. She may have even powdered her nose with it for the photo of her which graced the cover of the catalog for “New Race Records”. Race records were 78 rpm phonograph records made by and for African Americans, particularly during the 1920s and 1930s. Billboard magazine published “Race Records” charts between 1945 and 1949, finally dropping the term (at the suggestion of journalist Jerry Wexler) in June 1949 and replacing it with “Rythm & Blues Records”.

between 1945 and 1949, finally dropping the term (at the suggestion of journalist Jerry Wexler) in June 1949 and replacing it with “Rythm & Blues Records”.

Ethel Waters was born the child of a teen-aged rape victim on Halloween 1896. Young Ethel didn’t have any adult supervision to speak of, yet she managed to look after herself. She began, as had many of her contemporaries, performing at church functions. By the time she was a teenager she was renowned locally for her “hip shimmy shake”.

The shimmy was first introduced to Americans in 1883 at the Colombian Exposition Chicago World’s Fair by Farida Mazar Spyropoulous, aka “Little Egypt” (she was actually Syrian). Farida mesmerized audiences with the dance she referred to as the Hoochee-Coochee, or the shimmy and shake. Americans had not yet become familiar with the term belly dance, an entertainment which had first been seen by the French during Napoleon’s incursions into Egypt — the French called the dance danse du ventre (dance of the belly).

The shimmy was first introduced to Americans in 1883 at the Colombian Exposition Chicago World’s Fair by Farida Mazar Spyropoulous, aka “Little Egypt” (she was actually Syrian). Farida mesmerized audiences with the dance she referred to as the Hoochee-Coochee, or the shimmy and shake. Americans had not yet become familiar with the term belly dance, an entertainment which had first been seen by the French during Napoleon’s incursions into Egypt — the French called the dance danse du ventre (dance of the belly).

When people refer to hoochee-coochee (it’s spelled about six different ways) today they generally mean an erotic, highly suggestive dance, which isn’t quite the same as the dance that Little Egypt was performing in 1883.

Even during the Roaring Twenties the Shimmy raised eyebrows. But when Ethel Waters and Earl “Snake Hips” Tucker “shook the shimmy” in New York cabaret floorshows, it soon became a craze that swept the nation!

Earl “Snake Hips” Tucker was often billed as “The Human Boa Constrictor”. I would have thought that “The Human Cobra” would have been more apt.

In any case, critics of the day were hard pressed to find the right words to describe the movements that Earl was making on stage. I guess it wasn’t polite to discuss the shimmy in print.

In the 1933 pre-code film “Hoop-La”, Clara Bow portrays a hula/hootchee dancer at a carnival. Now THAT is a hootchee costume!

A few decades after Earl “Snake Hips” Tucker writhed his way across a stage, Elvis Presley’s pelvis would get him into a bit of trouble with the critics, and prompt a letter from a Catholic diocese to J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI!

After a show in La Crosse, Wisconsin, an urgent message on the letterhead of the local Catholic diocese’s newspaper was sent to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. It warned that “Presley is a definite danger to the security of the United States. … [His] actions and motions were such as to rouse the sexual passions of teen-aged youth… After the show, more than 1,000 teenagers tried to gang into Presley’s room at the auditorium. … Indications of the harm Presley did just in La Crosse were the two high school girls … whose abdomen and thigh had Presley’s autograph.”

Before “Sweet Georgia Brown” became a line of cosmetics, it was a snappy tune written in 1925 by Ben Bernie & Maceo Pinkard (music) and Kenneth Casey (lyrics).

“NO GAL MADE HAS GOT A SHADE

ON SWEET GEORGIA BROWN,

TWO LEFT FEET, OH, SO NEAT,

HAS SWEET GEORGIA BROWN!”

I had hoped that Elvis and Ethel had more than swiveling hips in common so I looked for a performance of “Sweet Georgia Brown” by The King. No such luck. But I did find an interesting recording from the early 1960s.

On May 24, 1962 The Beatles recorded the instrumental track (with backing vocals) on a version of “Sweet Georgia Brown” for musician Tony Sheridan. Sheridan had met The Beatles in Hamburg, Germany at a club owned by Bruno Koschmieder. Sheridan liked The Beatles, and the feeling was mutual; in particular on the part of George Harrison who never missed an opportunity to jam with Tony.

Sadly, Sweet Georgia Brown face powder no longer exists; however, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that Sweet Georgia Brown hair pomade is once again available! There are three different varieties, so one of them is bound to be perfect for your man’s classic pompadour.