Mon 12 Jul, 2010

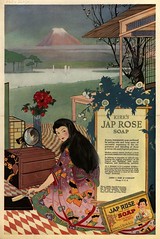

JAP ROSE

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: Commodore Perry, Gerald Ford, Gilbert and Sullivan, Girl Scout, Iva Ikuko toguri D'Aquino, Kirks, Methodist, Pears, The Mikado, Tokyo Rose, Topsy Turvy, UCLA, WWII, zoology

From the mid-1600s until 1854 Japan had been, by choice, a very isolated nation. They may have continued their isolation for another 200 years if it had not been for the Treaty of Kanagawa (aka Perry Convention). The treaty was signed by the Japanese under pressure from U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry. In 1853 he had sailed into Tokyo Bay with a fleet of warships and had demanded that the Japanese open their ports to U.S. ships for supplies. It was clear to the Japanese that the Commodore would return and make things very unpleasant for them if they didn’t capitulate. The Japanese signed similar treaties with Britain, France, and Russia.

Ad is circa 1918

As a result of these new trade agreements, Westerners became obsessed with all things Japanese. One of the things that intrigued Westerners the most were the bathing habits of the Japanese. At a time when folks in the U.S. were setting aside a few moments on a Saturday to scrub themselves clean of a week’s accumulation of grime, the Japanese were bathing daily and, rumor had it, frequently more than once each day!

The West, specifically the Caucasian West, felt that they were morally superior to nearly everyone else on the planet. How alarming it must have been for them to reflect on “Cleanliness is next to godliness” – and realize that they’d fallen way behind the Japanese in honoring that virtue.

Companies such as Pear’s in the U.K., and Kirk’s in the U.S. jumped on the cleanliness bandwagon. Instead of homemade soap used for everything from cleaning the day’s dishes to washing mom’s hair, personal bars of soap were being marketed with slogans such as “Have you used Pear’s soap today?”

The West’s fascination with Japan wasn’t confined to bathing habits, and it wasn’t an obsession of a few months duration.

Years after the treaties, on March 14, 1885, the Gilbert & Sullivan comic opera “The Mikado” opened in London. It ran at the Savoy Theater for 672 performances! Here’s a video, from the 1999 film “Topsy Turvy” a fictionalized account of the creation of the Mikado.

Many Japanese were understandably ambivalent about the Mikado; however, maybe people were too quick to assume that all Japanese would be offended. When Prince Fushimi Sadanaru made a state visit in 1907, the British government banned performances of The Mikado from London for six weeks, fearing that the play might offend him—a maneuver that backfired when the prince complained that he had hoped to see The Mikado during his stay. A Japanese journalist covering the prince’s stay attended a proscribed performance and confessed himself “deeply and pleasingly disappointed.” Expecting “real insults” to his country, he had found only “bright music and much fun.”

In 1947 General Douglas MacArthur banned a large-scale professional production of Mikado in Tokyo by an all-Japanese cast. I’m surprised that MacArthur was even aware of the proposed production; after all he was busy being in command of the occupation forces, as well as undertaking the democratization of Japan – complete with a ratified Constitution and the enfranchisement of women.

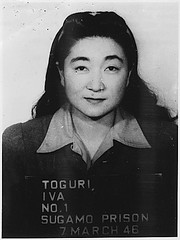

None of this meant much to Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino, or as she would forever become known, Tokyo Rose.

None of this meant much to Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino, or as she would forever become known, Tokyo Rose.

Iva was born in Los Angeles, she was a Girl Scout, a Methodist, and she had graduated from UCLA with a degree in zoology. In other words, Iva was an all-American girl. She left for Japan in July 1941, possibly to care for an ailing relative, or to attend medical school.

Iva had been issued a Certificate of Identification, she didn’t have a passport. In September 1941 she applied to the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan for a passport, but she’d not received an answer by the December 7, 1941 attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor. She was stranded in Japan for the duration.

Iva was pressured by the Japanese Central Government to renounce her U.S. citizenship; she refused. She risked her life to provide POWs with food. By 1943 she, and prisoners of war, were coerced into producing radio broadcasts intended to demoralize the U.S. troops. She participated, but would not speak against the United States – and at no time did she refer to herself as Tokyo Rose. The name was a catch all used by U.S. troops to describe all of the women who made the propaganda broadcasts.

Iva was arrested at the end of the war and thoroughly investigated by the FBI. The FBI concluded that: “the evidence then known did not merit prosecution”.

Even so, in 1949 Iva was tried in San Francisco for treason. She was found guilty on one count, that on a certain date in 1944 she “did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships.” She was fined $10,000 and given a 10-year prison sentence. Attorney Collins called the verdict “Guilty without evidence”. She was sent to the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia. She was paroled after serving six years and two months, and released January 28, 1956.

She was granted a full and unconditional Presidential pardon by Gerald Ford on January 19, 1977, his last full day in office. She passed away on September 26, 2006; she was 90.