Wed 20 Oct, 2010

ALMA

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: Alma Mahler, Austria, Brunhilde, fin de siecle, Franz Werfel, Gustav Klimt, Gustav Mahler, love doll, Oskar Kokoschka, sex toys, Vienna, Vienna Secession, Walter Gropius

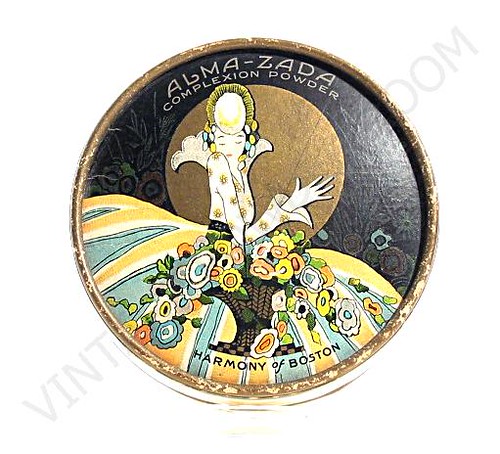

Beautiful, colorful, and feminine, the ALMA face powder box (manufactured by Harmony of Boston) reminds me of a woman who possessed those qualities and a few more during her life time; Alma Maria Mahler Gropius Werfel.

Alma’s maiden name was Schindler and she was born on August 31, 1879. Alma was a socialite who became well known in her youth for her beauty and vivacity. She became the wife, successively, of composer Gustav Mahler, architect Walter Gropius, and novelist Franz Werfel, as well as the consort of several other prominent men.

During her childhood and into her teens Alma played piano and composed music – some of which survives and is still performed today. Alma was a pretty little girl, however it was in fin de siecle Vienna that she grew into a woman of legendary beauty, often referred to as “The Most Beautiful Girl in Vienna”.

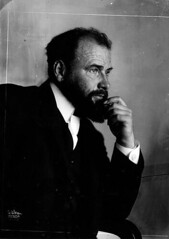

Alma’s first serious love affair was with the artist Gustav Klimt (a member of the group of artists known as the Vienna Secession) when she was 17 years old.

It’s not clear if Alma had serious aspirations as a musician/composer – in any case her marriage in 1902 to Gustav Mahler (19 years her senior) caused her to shift her focus from her own creative needs to the care and emotional support of her famous husband. Her role as muse is one she would play repeatedly throughout her life. Her infidelities and multiple marriages suggest to me that being the wife or consort of a creator, rather than making art herself, may have caused her great frustration. If she couldn’t attain fame and success on her own merit, then she could align herself with powerful and talented men over whom she could exert a degree of influence.

A few years into her marriage to Mahler the couple lost their five year old daughter, Maria, to scarlet fever and diphtheria. Alma’s grief led her into an affair with the young architect Walter Gropius (who would later become the head of Bauhaus) whom she met at a spa.

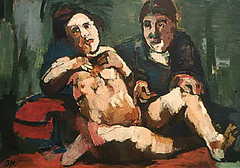

Following Mahler’s death in 1911 Alma didn’t immediately turn to Gropius, rather she began an affair with the tempestuous artist Oskar Kokoschka, who created many works inspired by his relationship with her, including his painting Bride of the Wind. Kokoschka was intensely possessive and jealous, and Alma grew weary of his constant demands for her time and attention.

It’s likely that Alma breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Kokoschka enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian Army. The absence of her obsessed and unstable lover gave her an opportunity to distance herself from him, and she subsequently resumed her relationship with Gropius. Gropius, like Koskoschka, was serving in combat during WWI. She and Gropius married in 1915 during one of his military leaves.

Kokoschka was undoubtedly a handful. He was also, in my opinion, her most interesting entanglement. When he got the news that Gropius and Alma had been married he immediately ordered a life sized doll of her be made to his specifications! Yes, Alma may have been the first “real doll”.

To understand fully the extent of Oskar’s mania for Alma, below is the letter he wrote to the doll maker Hermine Moos.

“Yesterday I sent a life-size drawing of my beloved and I ask you to copy this most carefully and to transform it into reality. Pay special attention to the dimensions of the head and neck, to the ribcage, the rump and the limbs. And take to heart the contours of body, e.g., the line of the neck to the back, the curve of the belly. Please permit my sense of touch to take pleasure in those places where layers of fat or muscle suddenly give way to a sinewy covering of skin. For the first layer (inside) please use fine, curly horsehair; you must buy an old sofa or something similar; have the horsehair disinfected. Then, over that, a layer of pouches stuffed with down, cotton wool for the seat and breasts. The point of all this for me is an experience which I must be able to embrace!”

Later Kokoschka eagerly demanded of Moos: “Can the mouth be opened? Are there teeth and a tongue inside? I hope so!”

Kokoschka, being a thoughtful lover, rushed out to purchase Parisian clothes and lingerie for his ersatz amour. Given all of his efforts, was Oskar surprised by the Alma-doll’s lack of reciprocal passion? There came a time when he realized that the doll would never be the loving surrogate companion he’d longed for – and it was then that Oskar decided to use her as a model for some of his paintings.

Ultimately Oskar used the Alma-doll (which was constructed of wood and fabric) as an effigy and beheaded it at a bacchanal at his atelier in Dresden. Any of us who have suffered through an unfortunate affair can surely understand the catharsis of the symbolic beheading of a former flame. In fact, why didn’t I ever think of that?

There is one problem with beheading an effigy; some of your neighbors may think that a murder has actually been committed! The morning after the party the police arrived at Oskar’s door demanding an explanation for the reported homicide which, once given, could not have put them much at ease. At least Oskar was free of his obsession. He described the end:

“The dustcart came in the grey light of dawn, and carried away the dream of Eurydice’s return,”Kokoschka remembered. “The doll was an image of a spent love that no Pygmalion could bring to life.”

Meanwhile Alma didn’t find it difficult to remain faithful to Gropius; she found it impossible! She embarked upon an affair with the Prague born poet and writer Franz Werfel. Alma became pregnant and in 1918 she gave birth to a son, Martin Carl Johannes Gropius. Martin, born prematurely, survived only ten months. And to compound Gropius’ grief over his loss he’d discovered Alma’s affair with Werfel, which gave him cause to question Martin’s paternity.

Alma’s marriage to Gropius didn’t survive much past Martin’s death, and by 1920 she and Werfel began to openly live together. For some reason Alma wasn’t in a marrying frame of mind and postponed tying the knot with him until 1929. She did, however, refer to herself during the nine years as “Alma Mahler-Werfel (dropping “Gropius” like a burning match). In 1938 Alma and Werfel, who was Jewish, fled Austria ahead of the Nazis. After an arduous journey, much of it by foot over the Pyrenees, the couple immigrated to the U.S., finally settling in Los Angeles.

There are lots of things that have puzzled me about Alma, but one of the most confounding was how she, a lifelong anti-Semite, had ever married Werfel in the first place. His talent must have been significant enough to allow Alma to ignore her bigotry.

By most reports it appears that Alma was a vain and contentious woman who lacked empathy and, as such, she found it particularly difficult to age gracefully. Her son-in-law, Ernst Krenek described her as:

“…a magnificently tarted-up battleship. She was accustomed to wearing long, flowing garments in order not to show her legs, which were perhaps a less remarkable detail of her physiognomy. Her style was that of Wagner’s Brunhilde transported into the atmosphere of Johann Strauss’ Fledermaus.”

Werfel died in Los Angeles in 1945 while correcting galley proofs of his last book of verse. In 1951 Alma moved to New York to complete her autobiography, which she’d begun in the late 1940s. She’d hired a ghost-writer who fell out with her because of her anti-Semitism and her attacks on people who were still living. The book, ironically titled “And the Bridge is Love”, was published first in English and wasn’t the success Alma had hoped for. In fact her book was criticized for being salacious, ambiguous, and contradictory. Which immediately places it on my “must read” list.

By the time that a German version of the book was being prepared for publication a few of Alma’s friends, including Thomas Mann, had already distanced themselves from her.

Alma, of the many surnames, passed away on December 11, 1964 at the age of 85.

NOTE: Much of the information for this post was gleaned from Wikipedia, and from:

Psychedelic art shared a similar aesthetic with its predecessor.

Psychedelic art shared a similar aesthetic with its predecessor.

Even though it was Mucha who produced posters of the “Divine Sarah”, she may have had more in common with Aubrey Beardsley. Both of them were extreme personalities, flamboyant and eccentric. Beardsley expressed himself quite often by donning outlandish garments, and Bernhardt frequently slept in a coffin so that she could “better understand my tragic roles”.

Even though it was Mucha who produced posters of the “Divine Sarah”, she may have had more in common with Aubrey Beardsley. Both of them were extreme personalities, flamboyant and eccentric. Beardsley expressed himself quite often by donning outlandish garments, and Bernhardt frequently slept in a coffin so that she could “better understand my tragic roles”.