Thu 7 May, 2009

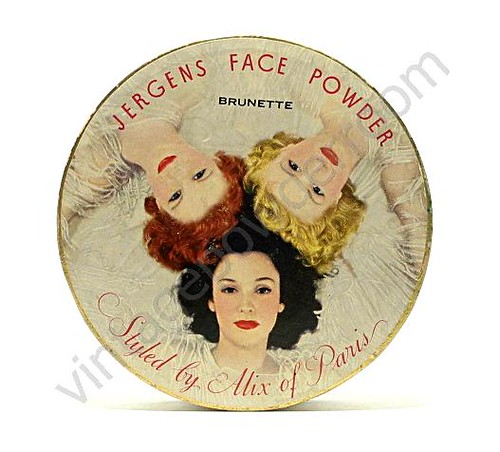

JERGENS

Comments (0) Filed under: Advertisements, Face Powder BoxesTags: 1940s, Betty Grable, home front, Jane Russell, Lipstick, pin-up, propaganda, Rita Hayworth, Rosie the Riveter, victory garden, WWII

The roles that women played during World War II were as complex and contradictory as at any time in history. On the home front they were wives, mothers, sweethearts, factory workers, and taxi drivers. War time propaganda encouraged women to keep the home fires burning, while simultaneously raising children and driving rivets into the hull of a destroyer or the fuselage of a bomber.

I have noticed that one phrase appeared consistently in wartime articles on make-up and fashion, and that was “morale is woman’s business”. It was made clear that in addition to any other responsibilities she may have had, it was a woman’s patriotic duty to look her best at all times. The business of morale was taken seriously, and countless articles were written to advise women on how to be competent, effective war workers, and yet remain attractive and cheerful companions.

While the women of the home front were keeping things on track, servicemen needed to be reminded why they were fighting, and what they were fighting for; and nothing sent a clearer message than a gorgeous pin-up picture. Hollywood stars Rita Hayworth, Jane Russell and Betty Grable were the three most popular pin-up girls of the era, and their photos accompanied soldiers in their footlockers around the world. Five million copies of Rita Hayworth’s picture were sold; that number exceeded only by Betty Grable’s iconic photo.

While the women of the home front were keeping things on track, servicemen needed to be reminded why they were fighting, and what they were fighting for; and nothing sent a clearer message than a gorgeous pin-up picture. Hollywood stars Rita Hayworth, Jane Russell and Betty Grable were the three most popular pin-up girls of the era, and their photos accompanied soldiers in their footlockers around the world. Five million copies of Rita Hayworth’s picture were sold; that number exceeded only by Betty Grable’s iconic photo.

Photos from home were crucial to a fighting man’s morale, but sometimes a candid snapshot wasn’t good enough. I found an article in the Los Angeles Times from October 1943 entitled “Send Him Your Picture”. The article described in detail how to apply make-up for a professional portrait, and it also provided tips on what to wear and whether or not to apply whitener to your teeth. This all speaks to the significance of the pin-up photo during the war. The pin-ups weren’t merely masturbatory tools for lonely troops, but they were a necessary, if idealized, connection to home.

Not surprisingly, the focus of home front culture was on victory. There were victory gardens, victory pins (to wear on your sweater or jacket), and there was victory lipstick. Victory lipstick came in tubes made of paper, plastic, or wood because metal was required for the war effort.

Not surprisingly, the focus of home front culture was on victory. There were victory gardens, victory pins (to wear on your sweater or jacket), and there was victory lipstick. Victory lipstick came in tubes made of paper, plastic, or wood because metal was required for the war effort.

Jergens wasn’t alone in using patriotic themes in their advertising, but they put an imaginative spin on it when they hired world class pin-up artist Alberto Vargas to create both a package design and an ad that urged women to “be his pin-up girl”. And of course it was Vargas, among other pin-up artists, who inspired some truly glorious nose art (art that graced the fuselage of many of the aircraft during the war).

It’s plain to see that Jergens grasped the relationship between pin-up art and the woman’s business of morale and used it masterfully to their advantage.

The pin-up girl ad campaign appears to have run during 1944, and the face powder box with the Vargas art turns up in ads for about a year following the end of the war in 1945.