Mon 24 Jan, 2011

GOSSAMER

Comments (1) Filed under: Advertisements, Face Powder BoxesTags: 1890s, Andrew Carnegie, Gilded Age, Isadora Duncan, Jennie Jerome, John Churchill, Lady Randolph Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill, Mark Twain, Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, snake tatoo, Tetlow Mfg Company, Winston Churchill

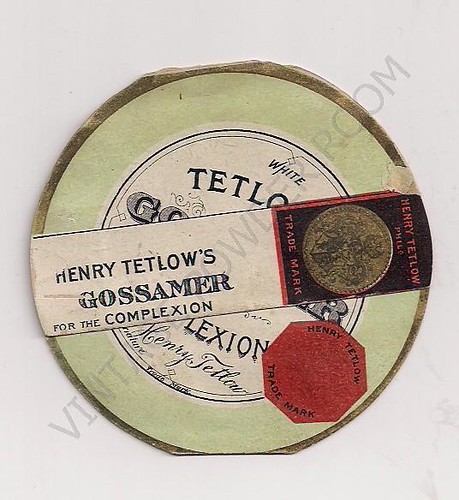

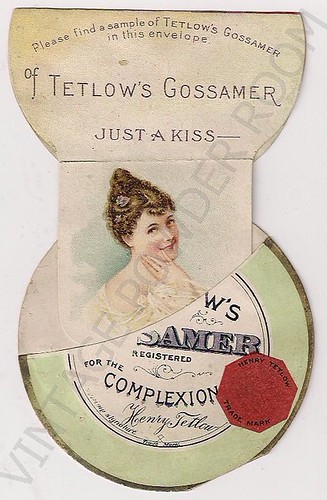

The most recent addition to my collection is an exquisite sample envelope for Henry Tetlow’s GOSSAMER face powder.

Gossamer debuted in 1888 and the sample envelope in the photo has a copyright date of 1895, which means that it was available during the “Gilded Age”.

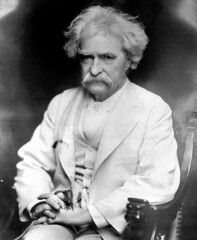

The term ‘Gilded Age’ was coined by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in their 1873 book, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. The name refers to the process of gilding an object with a superficial layer of gold and is meant to make fun of ostentatious display while playing on the term golden age.”

“What is the chief end of man?–to get rich. In what way?–dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must.”

— Mark Twain-1871

Mark Twain’s quote accurately sums up the Gilded Age; it was an era during which every man was a potential Andrew Carnegie. The Americans who achieved great wealth flaunted it in ways that would have cost them their heads in 18th Century France. One of the most outrageous examples of enormous wealth, coupled with a profound lack of taste, was at a dinner party thrown by Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish to honor her dog – who arrived sporting a $15,000 [$389,637.70 in today’s dollars!] diamond collar.

To put that kind of money into perspective, while Mrs. Fish’s spoiled pooch wore diamonds, many human Americans wore rags. In 1890, 11 million of the nation’s 12 million families earned less than $1200 per year [$28,818.49 current U.S. dollars]; of this group, the average annual income was $380 [$9,125.85 current U.S. dollars], well below the poverty line.

Of the women who would become well-known during the Gilded Age, one would leave her mark on history – and that woman was Jennie Jerome.

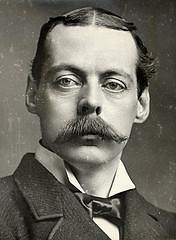

Jennie was born Jeanette Jerome in Brooklyn, New York on January 9, 1854. Jennie’s first marriage was to Lord Randolph Churchill, the second son of John Winston Spencer-Churchill, the 7th Duke of Marlborough and Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane. The couple wed on 15 April 1874, at the British Embassy in Paris.

Jennie had the money and the time to indulge her wild side. There was a persistent, unverifiable, rumor that she’d had a tattoo of a snake twined around her wrist, which she would hide with a bracelet when required.

Even if the rumor of a tattoo is false, Jennie’s wild side would lead her into numerous affairs while she was married to Lord Randolph Churchill. Among Lady Randolph’s conquests were Karl Kinsky (aka Karl, 8th Prince Kinsky of Wchinitz and Tettau) and King Edward VII of England.

Lady and Lord Randolph had two sons: Winston (born less than eight months after the marriage) and John. Jennie’s sisters believed that John’s biological father was Evelyn “Star” Boscawen, 7th Viscount Falmouth.

Known in society for her intelligence and wit, Jennie’s affairs not only provided her with excitement, but they enabled her to make the kinds of connections that would help Lord Randolph, and later Winston, in their careers.

Lady Randolph played a limited role in her sons’ upbringing – a hands off approach to child rearing was typical of the day for women in her social circle. Winston had a nanny, Mrs. Elizabeth Everest, whom he adored – however he worshipped his mother. He’d frequently write to Jennie, begging her to visit him, which she rarely did. Their relationship changed after Winston became an adult; the two became friends and allies. Winston came to view his mother as his advisor and political mentor.

Lord Randolph died in 1895 at age 45, reportedly of syphilis, although given his symptoms it’s been hypothesized that he actually succumbed to a tumor deep within the left side of his brain. The hypothesis of a brain tumor is credible, particularly when you consider that neither Jennie, nor her sons, exhibited any signs of syphilis.

On July 2, 1900 Jennie married George Cornwallis-West, a captain in the Scots Guards who was the same age as her son Winston! Neither John nor Winston was particularly thrilled with Jennie’s choice of a husband, primarily due to the age difference. Even with the difference in their ages, the marriage lasted for twelve years; the couple was separated in 1912 and was divorced in 1914.

Jennie remained single until June 1, 1918 when she was married to Montague Phippen Porch, a member of the British Civil Service in Nigeria. If John and Winston were dismayed by her marriage to Cornwallis-West, they must have been apoplectic when she wed Porch — he was three years Winston’s junior!

Personally, I think the “boys” should have lightened up. It sounds to me as if Jennie aged chronologically, but retained a youthful outlook and personality that drew the younger men to her. Perhaps a man her own age couldn’t have kept up with her!

Jennie was 67 years old when she slipped while descending a friend’s staircase; she was wearing new high heeled shoes. She broke her ankle and gangrene set in and her left leg was amputated above the knee. She died soon afterward in her home in London following a hemorrhage of an artery in her thigh (a direct result of the amputation).

Six years later there would be another freak clothing-related death of a prominent woman. On September 14, 1927 Isadora Duncan (whom many consider to be the creator of modern dance), was riding in an open car when one of her signature long, flowing scarves became entangled around one of the vehicle’s open-spoke wheels and rear axle, breaking her neck.

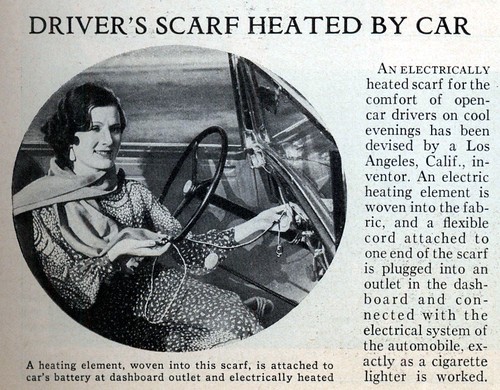

While searching for a photo of Isadora Duncan, I found the nifty photo of the plug-in heated scarf. Does it have anything to do with Isadora’s death? Not really; I was just enamored of the advertisement.

However, whether you favor a traditional scarf, or one of the plug-in varieties, I must advise you to accessorize with caution.