Tue 17 Aug, 2010

GOLDEN GATE HAIR NET

Comments (0) Filed under: Hair Net PackagesTags: Agatha Christie, Charlie Chan, Chinatown, Dashiell Hammett, Dorothy Sayers, Earl Derr Biggers, Grant Street, HUAC, Jane Fonda, Jason Robards, Lillian Hellman, Muriel Gardiner, Raymond Chandler, Ronald Knox, San Francisco, The Hollywood Ten, The Maltese Falcon, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Vanessa Redgrave

The first thing that this hair net package calls to mind is obviously the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco; but it actually bears some resemblance to the Grant Street Gate to that city’s Chinatown.

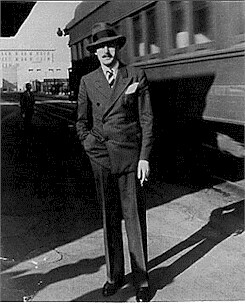

My initial impulse when I sat down to write this post was to follow a straight line from the Golden Gate Bridge to Chinatown, but my thinking is rarely stays that linear. After a few minutes I realized that what San Francisco means to me, other than 1960s psychedelic bands, is Sam Spade.

The novel THE MALTESE FALCON, featuring the character of Sam Spade, was written by Dashiell Hammett and was published in 1930 – during the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.

The golden age of detective fiction is generally considered to be those years between the World Wars. Many of the writers of the Golden Age were British (e.g. Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers); however, Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett were successfully writing classic American detective stories during that period. Today Hammett and Chandler are two of the best known of the era’s hard-boiled detective fiction authors.

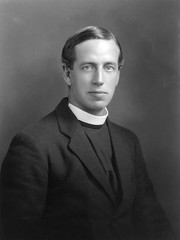

As early as 1929, writers were attempting to define the mystery/detective genre. Ronald Knox, an English theologian, priest and crime writer published some rules for writing detective fiction.

According to Knox a detective story: “must have as its main interest the unraveling of a mystery; a mystery whose elements are clearly presented to the reader at an early stage in the proceedings, and whose nature is such as to arouse curiosity, a curiosity which is gratified at the end.”

Knox’s “Ten Commandments” (or “Decalogue”) are as follows:

- The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.

- All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

- Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

- No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

- No Chinaman must figure in the story.

- No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

- The detective himself must not commit the crime.

- The detective is bound to declare any clues which he may discover.

- The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal from the reader any thoughts which pass through his mind: his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

- Twin brothers and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

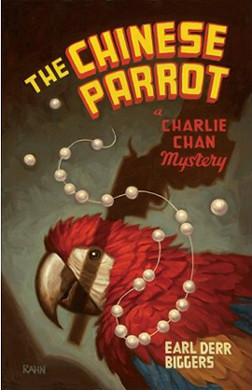

Rule number five is particularly odious. No Chinaman? What happens when the detective is a Chinaman? Earl Derr Biggers created Charlie Chan during the 1920s. There are many reasons to be offended by the portrayal of Chan both in the books and in the subsequent films; however, I think a good rule of thumb is to never apply today’s sensibilities to yesterday’s literature. My reading list would shrink to nearly nothing if I did that. I look at the stories in the context of their time, and by putting Charlie Chan in a position of authority I believe that Biggers was taking an interesting, and somewhat risky step forward.

Rule number five is particularly odious. No Chinaman? What happens when the detective is a Chinaman? Earl Derr Biggers created Charlie Chan during the 1920s. There are many reasons to be offended by the portrayal of Chan both in the books and in the subsequent films; however, I think a good rule of thumb is to never apply today’s sensibilities to yesterday’s literature. My reading list would shrink to nearly nothing if I did that. I look at the stories in the context of their time, and by putting Charlie Chan in a position of authority I believe that Biggers was taking an interesting, and somewhat risky step forward.

Quoting from Wikipedia: “Interpretations of Chan by critics are split, especially as relates to his ethnicity. Positive interpretations of Chan argue that he is portrayed as intelligent, benevolent, and honorable, in contrast to most depictions of Chinese at the time the character was created. Others argue that Chan, despite his good qualities, reinforces Chinese stereotypes such as poor English grammar, and is overly subservient in nature.” I’ll leave the debate on ethnicity and stereotypes to others.

Rule number seven was probably meant to discourage other writers from doing what Agatha Christie had done so successfully in 1926, which was to write a detective novel in which the narrator turns out to be the killer. The novel, THE MURDER OF ROGER ACKROYD, has been considered by many to have been Christie’s masterpiece.

In 1930 Agatha Christie published her first Miss Marple novel, MURDER AT THE VICARAGE, (a classic “cozy”) and Dashiell Hammett published THE MALTESE FALCON, the only novel to feature Sam Spade and, arguably, the novel that first introduced the archetype of the hard-boiled detective to the world. In the novel Spade is cynical, bitter, and morally ambiguous, that is until he explains to Brigid O’Shaunassey his reasons for turning her in. Spade’s moral code may be non-traditional, but he adheres to it. Spade tells her that he had fallen for her, but she had murdered his partner. He’d never be able to trust her, and he’d likely go to prison with her if he concealed what he knew from the cops. Finally Spade tells Brigid that he’ll wait for her; provided she doesn’t hang.

Hammett not only created the modern private detective, but he created two of my favorite film characters, Nick and Nora Charles. Hammett wasn’t quite as enamored of the THIN MAN films as I am, but they did provide him with enough money to afford decent liquor, at least for a while. Who were Nick and Nora in real life? Hammett told his long-time companion, writer Lillian Hellman, that she was the inspiration for Nora. However, according to Hellman “Hammett said I was also the silly girl in the book and the villainess.”

Hellman and Hammett had a 30 year long relationship – a part of which was depicted in the 1977 film JULIA starring Jane Fonda, Jason Robards, and Vanessa Redgrave. Did Hellman really smuggle papers out of Nazi Germany in her hat as shown in the film, or had she taken another woman’s (i.e. Muriel Gardiner) story as her own? The jury is still out on whether or not Hellman greatly embellished her autobiographies.

In any case, JULIA was a compelling enough film to win three Oscars. I love the movie – the costumes are exquisite, the acting superb. It’s worth watching whether the story is Hellman’s or not. Oh, and look at this clip from the film with Meryl Streep as Anne Marie and Jane Fonda as Lillian.

During the 1950s Hammett was investigated by Congress, and testified on March 26, 1953 before the House on Un-American Activities Committee. Although he testified to his own activities, he refused to cooperate with the committee and was blacklisted.

Others refused, as did Hammett, to cooperate with HUAC and they paid dearly. A group of Hollywood writers who refused to cooperate with the committee became known as THE HOLLYWOOD TEN. They were Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott and Dalton Trumbo.

The ten men claimed that the First Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to refuse to answer questions about their beliefs. The HUAC and, subsequently, the courts disagreed and all ten men were found guilty of contempt of congress. Each of them was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison.

Hellman had appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950. At the time, HUAC was well aware that Dashiell Hammett had been a Communist Party member. Asked to name names of acquaintances with communist affiliations, Hellman delivered a prepared statement which read in part:

“To hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions, even though I long ago came to the conclusion that I was not a political person and could have not comfortable place in any political group.”

Hellman may have embellished her autobiographies, but her statement to HUAC leads me to believe that she was also a stand-up dame.

About Hammett’s writing career, Hellman said:

“I have been asked many times over the years why he did not write another novel after The Thin Man. I do not know. I think, but I only think, I know a few of the reasons: he wanted to do a new kind of work; he was sick for many of those years and getting sicker. But he kept his work, and his plans for work, in angry privacy and even I would not have been answered if I had ever asked, and maybe because I never asked is why I was with him until the last day of his life.”

I’ve never been able to visit San Francisco without thinking of Dashiell Hammett or Sam Spade. Even though Hammett never wrote another novel after THE THIN MAN, his contribution to mystery fiction, in particular to the hard-boiled genre, was seminal.

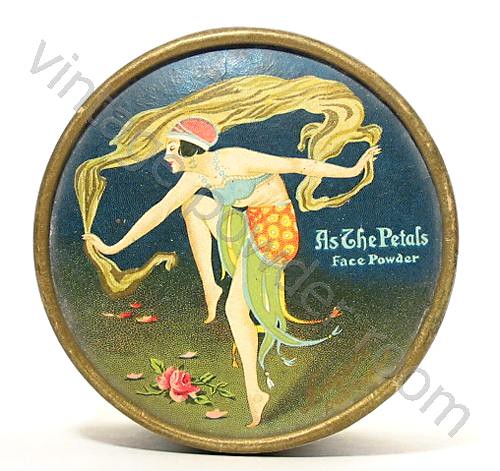

On September 14, 1927, Isadora wrapped a long hand painted silk scarf around her neck and got into a car with Italian mechanic, Benoît Falchetto. As the car pulled away Isadora waved to a group of friends, reportedly saying “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire!” (“Goodbye, my friends, I am off to glory!”). The scarf fluttered dramatically behind her, but as the car picked up speed it became entangled in the spokes of one of the wheels and tightened around Isadora’s neck. The dancer was yanked out of her seat and over the rear of the car, and then dragged along the cobblestone street to her death.

On September 14, 1927, Isadora wrapped a long hand painted silk scarf around her neck and got into a car with Italian mechanic, Benoît Falchetto. As the car pulled away Isadora waved to a group of friends, reportedly saying “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire!” (“Goodbye, my friends, I am off to glory!”). The scarf fluttered dramatically behind her, but as the car picked up speed it became entangled in the spokes of one of the wheels and tightened around Isadora’s neck. The dancer was yanked out of her seat and over the rear of the car, and then dragged along the cobblestone street to her death.