Tue 24 Nov, 2009

Thu 19 Nov, 2009

Lady, be Lovely – Hollywood Miracle

Comments (0) Filed under: UncategorizedTags: 1930s, Ginger Rogers, Greta Garbo, Hollywood

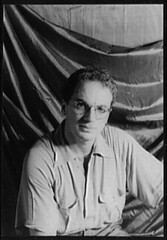

The above drawings represent the “Evolution of Garbo” as interpreted by Anne Rodman in her beauty book, “Lady, be Lovely”. I can’t say that I immediately identified the subject of the drawings as Garbo, but I can certainly appreciate a Hollywood Miracle when I see one. Below is a portrait of Greta Garbo which looks similar to the first of Anne’s drawings.

An early portrait of Greta Garbo

On page 12, Anne Rodman uses Ginger Rogers to demonstrate how women may develop their beauty with “thought and study” and the “aid of clever make-up and eye catching coiffures”.

Rodman’s advice makes sense to me — well applied makeup and a flattering hairstyle can make or break a look; but then a couple of paragraphs later she baffles me with the statement “…do not be a slave to fashion. Change your style every season if you would be young.” Huh?

Rodman’s advice makes sense to me — well applied makeup and a flattering hairstyle can make or break a look; but then a couple of paragraphs later she baffles me with the statement “…do not be a slave to fashion. Change your style every season if you would be young.” Huh?

Even though I’m obviously confused about what constitutes being a slave to fashion, I agree with Anne’s advice to women that they emphasize their individual beauty. Find your unique qualities and enhance them.

In any case, Ginger Rogers managed to develop a look that suited her perfectly, and she dazzled film goers for many years.

Mon 16 Nov, 2009

WEST ELECTRIC HAIR NET

Comments (1) Filed under: Hair Net PackagesTags: 1920s, Agatha Christie, Angelus Temple, evangelist, Foursquare Church, kidnapping, Pentecostal Church, Salvation Army, Venice Beach

The design on the hairnet package above is emblematic of the 1920s in Southern California: surf, sand, sun and sin. What? You don’t see any sin in the design? I guess it’s just my evil mind — the first thing that I thought of was Sister Aimee Semple McPherson’s mysterious disappearance from Venice Beach on May 18, 1926. What did her disappearance have to do with sin? Read on.

Southern California beaches weren’t just places from which to disappear in the 1920s — they were obviously places to relax (and to wear your prettiest bathing costume.) I was pleasantly surprised to discover a beautiful souvenir folder of Venice Beach which not only shows people enjoying a day at the beach, but echoes the design of the hairnet package. Note the similarities in the coloration and overall design — really quite nice.

Aimee was born Aimee Elizabeth Kennedy on October 9, 1890 on a farm in Canada. It was her mother, Mildred (Minnie), who first introduced young Aimee to religion. Minnie worked with the Salvation Army and her daughter would often accompany her to soup kitchens.

While other little girls may have preferred to play house with their dolls, Aimee played “Salvation Army” with hers. Sermonizing to a congregation of dolls may not have been particularly thrilling or rewarding, but it was good practice for her adult life.

Aimee and Robert Semple

Given her interest in religion and the fact that, even in high school, she was protesting the teaching of evolution in public schools, it’s no surprise that she fell for a Pentecostal missionary from Ireland, Robert James Semple.

She converted to her husband’s faith and they married on August 12, 1908. The newlyweds immediately took off on an evangelistic tour of Europe. Continuing their mission they arrived in Hong Kong, China in June 1910, where both contracted malaria. Robert died on August 19, 1910 and was buried in Hong Kong. Aimee was just beginning to recover from the same illness that took her husband when she gave birth to a daughter, Roberta Star Semple, on September 17, 1910.

Newly widowed and a recent mother, Aimee continued to convalesce in New York, and it was there that she met accountant Harold Stewart McPherson. They were married on May 5, 1912, and their son, Rolf, was born on March 23, 1913.

Aimee on the road

In mid-1915 Aimee took her act on the road and held tent revival meetings up and down the Eastern Seaboard, eventually heading out to other parts of the country. Whatever his reasons, Harold wasn’t always able to travel with his wife and their marriage suffered. In 1918 he filed a petition for divorce (citing abandonment) and the divorce was granted in 1921.

Aimee eventually tired of being on the road and settled in Los Angeles. Her ministry was so successful that she was able to build the Angelus Temple in Echo Park (dedicated in 1923).

Sister Aimee was at the zenith of her influence and popularity by 1926. And then it all began to unravel.

On May 18, 1926 McPherson went with her secretary to Ocean Park Beach, just north of Venice Beach, to swim. It was from there that Aimee vanished. Had she drowned? Her mother thought so. Aimee had been scheduled to preach later that day, but Minnie filled in. She ended her emotional sermon by telling the parishioners that “Sister is with Jesus”.

Mourners kept a seaside vigil for their beloved Aimee, but she did not emerge from the sea. Sadly, one parishioner drowned searching for McPherson, and a diver perished from exposure.

Mourners kept a seaside vigil for their beloved Aimee, but she did not emerge from the sea. Sadly, one parishioner drowned searching for McPherson, and a diver perished from exposure.

It didn’t take long for people to notice that Kenneth G. Ormiston, the engineer for Aimee’s radio station, KFSG, had disappeared as well. Some felt that Ormiston and McPherson had run off together — they had become very friendly.

A month passed when finally there was word of Aimee in the form of a ransom note delivered to her mother. The note demanded a half million dollars or else McPherson would be sold into “white slavery”. The note was signed “The Avengers”. Believing that her daughter was dead, Minnie tossed the letter.

On June 23rd, like a biblical prophet, Aimee staggered out of the desert into a Mexican town just across the border from Douglas, Arizona. Aimee’s story was that she’d been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held in a shack until she managed to escape, walking 13 hours to freedom.

On June 23rd, like a biblical prophet, Aimee staggered out of the desert into a Mexican town just across the border from Douglas, Arizona. Aimee’s story was that she’d been kidnapped, drugged, tortured, and held in a shack until she managed to escape, walking 13 hours to freedom.

There were several gaping holes in her story: her shoes were grass stained and showed no signs of a 13 hour desert trek and, furthermore, she’d disappeared from the beach clad only in a bathing suit, yet she had turned up following her abduction fully dressed and wearing her own wristwatch. To make matters worse, no sign of the shack where she was allegedly held was ever discovered. A grand jury convened on July 8, 1926, but they adjourned after 12 days saying they hadn’t enough evidence to proceed against the wandering minister. The Grand Jury reconvened when new evidence was uncovered. The evidence suggested that Aimee and Kenneth had been traveling together, and signing into motels along the way.

What had Aimee really been up to for over one month? Had she been kidnapped as she continued to maintain, or had she gone off to have an abortion, or heal from plastic surgery? We’ll probably never know. District Attorney Asa Keyes dropped all of the charges, thus ending any official investigation.

Despite the bad press she’d received Aimee continued her good works, but her reputation had been permanently damaged. Involved in a power struggle with her mother over control of the church, Aimee had a nervous breakdown in 1930.

David Hutton w/ballet dancers

McPherson would marry for a third time on September 13, 1931 to actor and musician David Hutton. Two days into the marriage the groom was sued for alienation of affection by Hazel St. Pierre. Hutton claimed never to have met Hazel, but she still managed to walk away with a settlement of $5,000. Things would get worse. Aimee was in Europe when she heard that Hutton was billing himself as “Aimee’s man” in his cabaret act. Let’s hope he wasn’t performing “The Ballad of Aimee McPherson”. David and Aimee were divorced on March 1, 1934.

On September 26, 1944 McPherson traveled to Oakland, California for a series of revivals. When her son went to her hotel room at 10 am the next morning to fetch her for her sermon, he found her unconscious. Aimee would die less than two hours later. The coroner was not able to conclusively determine the casue of death. Apparently Aimee had been taking sleeping pills (Seconal) and it is most likely that her death was the result of an accidental overdose.

On September 26, 1944 McPherson traveled to Oakland, California for a series of revivals. When her son went to her hotel room at 10 am the next morning to fetch her for her sermon, he found her unconscious. Aimee would die less than two hours later. The coroner was not able to conclusively determine the casue of death. Apparently Aimee had been taking sleeping pills (Seconal) and it is most likely that her death was the result of an accidental overdose.

I wonder if there was something in the air during 1926 that caused two very famous women to mysteriously vanish, and then to reappear without a credible explanation. The first woman was, of course, Aimee Semple McPherson — the second woman was famed mystery writer Agatha Christie!

On December 8, 1926 after being told by her husband Archie that he was in love with another woman and wanted a divorce, Agatha vanished. She’d left notes for both her husband and her secretary saying that she was going to Yorkshire. Her car was found abandoned and for a while it appeared that she’d been the victim of foul play.

About ten days later Agatha was identified as a guest at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel (now the Old Swan Hotel) in Harrogate. Agatha would never give a full account of her disappearance. Two doctors diagnosed her as suffering from amnesia. I believe it was the news of Archie’s infidelity that caused her to go off the rails for a while.

Max and Agatha

Archie and Agatha would divorce, and in 1930 she would marry an archaeologist Max Mallowan, whom she’d met on a dig in the Middle East. The Mallowans would have a long and happy marriage.

For a wonderful fictional account of how Agatha spent her missing days, watch the 1979 film “Agatha” starring Vanessa Redgrave and Dustin Hoffman.

Sun 15 Nov, 2009

The twenties were a time of change, and nothing was changing faster than the attitudes of young women regarding “powder and paint”. While makeup was never intended to be a political statement, whether or not to use makeup was becoming a highly charged issue for young women during the the 1920s. On the lighter side of the topic I found this story in the Los Angeles Times, dated March 22, 1923.

Thu 12 Nov, 2009

The Real Black Dahlia

Comments (0) Filed under: EventsTags: 1940s, 1947, Black Dahlia, Esotouric, make-up, makeup, murder

Elizabeth Short

This coming Saturday, November 14, 2009, it will once again be my pleasure to co-host Esotouric’s “The Real Black Dahlia” tour. The tour isn’t so much a “who done it” as it is an exploration of Beth’s last couple of weeks in Los Angeles.

My abiding interest in vintage cosmetics, social history, and crime led me to create a thumbnail sketch of Elizabeth Short’s personality based upon her choice of cosmetics. What was it about Beth’s make-up that set her apart from her contemporaries? Join us on Saturday and find out.

Beth Short's mugshot

Her make-up selections may have been unusual, but in many ways Beth Short was typical of a certain group of young women characterized as the “Children of the Night” by Caroline Walker in an interview she conducted with Lynn Martin (who had been one of Beth’s roommates in Hollywood). These young women floated from man to man, and occasionally from job to job (they weren’t often employed). They weren’t prostitutes, they were simply a part of the post-war generation who gravitated to Hollywood for reasons of their own. Maybe they believed what they’d seen in the movies, that Hollywood was glamorous place where a pretty girl could parlay her looks into riches and fame.

For the rootless young women in Beth’s set Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles were often desperately lonely places offering little more than dark barrooms in which to hang out and wait for a man to buy them a drink and dinner. Any of them could have ended as Beth did — dead and dismembered in a vacant lot in Leimert Park within view of the Hollywood sign.

Hollywood Boulevard

Join us on the tour and learn more about the woman at the heart of Los Angeles’ most infamous unsolved murder.

See YOU on the bus!

Tue 10 Nov, 2009

Lady, Be Lovely — A Matter of Viewpoint

Comments (0) Filed under: UncategorizedTags: 1930s, 1939, Duchess of Windsor, Wallis Simpson

I confess, once I started paging through “Lady, Be Lovely”, I couldn’t wait to post a few more pages from that delightful book.

Today we’ll learn, among other things, that beauty has a viewpoint, that the queen of beauty is love, and how to be courageous.

There’s also a quote from the sanskrit, accompanied by a drawing that is obviously Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor. I will devote more time to the Duchess in a future post on unconventional beauty.

Mon 9 Nov, 2009

Lady, be Lovely

Comments (0) Filed under: UncategorizedTags: 1930s, 1939, Adrian, Anita Loos, Anne Rodman, Cedric Gibbons, Claire Booth Luce, Jane Murfin, NARS, The Women

I have an extensive collection of books on every subject of feminine interest from vintage fashion to cosmetics. One of my favorites is “Lady, be Lovely” by Anne Rodman, published in 1939. According to the introduction Anne worked as a copy writer for some of the leading cosmetics firms in the U.S. She also had a background in commercial art. Taking as her inspiration the notion that beauty could be taught to women from the viewpoint of an artist, she began to create “before and after” cartoons so that “a woman could see at a glance how to improve her appearance, just as if she were seated before the mirror of the best salon expert on Fifth Avenue.” What a wonderful concept!

Anne Rodman’s book reminds me of the film “The Women“. Both the book and the film were released in 1939 and each deals in its own way exclusively with women.

The Women

The film was based upon a play by Claire Booth Luce, and was adapted for the screen by Anita Loos and Jane Murfin. The sets were glorious — designed by Cedric Gibbons; and the women themselves were utterly divine — dressed by Adrian. Adrian’s designs were highlighted in a Technicolor fashion show sequence which was frequently cut from modern screenings. With the exception of the fashion parade the film was shot in B/W. I would love to have seen Norma Shearer’s famously “Jungle Red” fingernails in color, but that is something left to the imagination. There is a NARS lipstick in Jungle Red that may be fun to try.

Because Anne’s book is so delightful, I’m going to share bits of it here on a regular basis. I don’t know about you, but I can always use beauty advice, even if it is 70 years old! Get ready to “Kiss and Make Up” — the topic which begins Rodman’s book.

Fri 6 Nov, 2009

IRRESISTIBLE LIPSTICK

Comments (0) Filed under: LipstickTags: 1930s, 1940s, alcoholism, Clifford Odets, Jessica Lange, Kill Bill, Kurt Cobain, lobotomy, mental illness, Quentin Tarantino, Seattle, Uma Thurman, Western State Hospital

In her false witness, we hope you’re still with us,

To see if they float or drown

Our favorite patient, a display of patience,

Disease-covered Puget Sound

She’ll come back as fire, to burn all the liars,

And leave a blanket of ash on the ground

I miss the comfort in being sad

— from “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle” by Kurt Cobain

There’s something about the woman on this lipstick card that reminds me of the actress Frances Farmer. Maybe it’s the caption as much as it is the picture.

Frances Farmer was an absolutely gorgeous blonde who first hit the newspapers when, as a drama student at the University of Washington in Seattle in April 1935, she won first prize in a subscription contest sponsored by a local radical labor newspaper “The Voice of Action”. The prize for winning the contest was a six week trip via ocean liner to Soviet Russia to see a production at the Moscow Arts Theater. Frances’ mother Lillian wasn’t thrilled about the trip, and she told reporters “There has been no break between Frances and me over the trip. My fight is with the Voice of Action for sending her to Russia where she will be thrown in full contact with people who will probably make every effort to persuade her to Communism.”

Frances Farmer was an absolutely gorgeous blonde who first hit the newspapers when, as a drama student at the University of Washington in Seattle in April 1935, she won first prize in a subscription contest sponsored by a local radical labor newspaper “The Voice of Action”. The prize for winning the contest was a six week trip via ocean liner to Soviet Russia to see a production at the Moscow Arts Theater. Frances’ mother Lillian wasn’t thrilled about the trip, and she told reporters “There has been no break between Frances and me over the trip. My fight is with the Voice of Action for sending her to Russia where she will be thrown in full contact with people who will probably make every effort to persuade her to Communism.”

Frances wasn’t necessarily persuaded to embrace Communism, but she became even more determined to pursue an acting career. She returned to the U.S. during the summer of 1935, and her first stop was New York where she sought to launch a career in the theater. What she found instead was a Paramount Pictures talent scout, Oscar Serlin (credited with discovering Fred MacMurray). Frances did so well in her screen test that she was signed to a seven year contract on her 22nd birthday, and she promptly moved to Hollywood.

While Frances had more than enough talent for Hollywood she never had the temperament. She was headstrong (as evidenced by her trip to Russia against her parents wishes), and she had very little tolerance for the studio system which was firmly in place during the 1930s. Under the studio system every aspect of an actor’s life was managed — not the kind of arrangement designed to bring out the best in Frances. She was quoted as saying “Hollywood is a madhouse. It consumes ambitious youngsters. There’s no time to consider anyone. Hollywood casts you, forces you, pushes you. If you survive you’re plain lucky.”

Very early on the studio machine began to spin the story of Frances’ trip to Russia into something less likely to draw negative attention to her, or her political leanings. Initial reports stated the truth, that Frances had won first prize in a subsciptions contest for Voice of Action — but immediately following her arrival in Hollywood the story was retold very creatively with Frances winning a trip to Europe as the first prize in a popularity contest!

Paramount didn’t realize that they had a tiger by the tail. Frances arrived in Hollywood in September 1935, and by February 1936 she’d eloped to Yuma, Arizona with fellow actor William Wycliffe Anderson (aka Leif Erickson). Friends said they were surprised by the elopement and Frances’ mother Lillian said she was “completely floored”.

Clifford Odets c. 1937

In 1937 Frances left her husband at home and went off to Connecticut to work in summer stock. There she was invited to appear in Clifford Odets’ play “Golden Boy”. As were many people in the 1930s, Odets was a Marxist and his work reflected his politics. Ironically, when called before the House on Un-American Activities in 1952, Odets avoided being blacklisted by disavowing his past Communist affiliations and naming names.

Clifford and Frances had an affair while she was in New York; however, he was married to Acadamey Award winning actress Luise Ranier and he refused to leave her. Frances and Luise had more in common than Odets — both were creative, stubborn, and each was often characterized as “temperamental” by studios that were in the business of trying to crank out hits (particularly during the years of the Depression) and were not so much interested in whether a story had artistic merit.

After her affair with Odets soured Frances returned to her husband, Leif, in Los Angeles. The marriage began to crumble and talk of a divorce turned up in a few gossip columns by November 1939. In fact over the next couple of years the two were referred to in the newspapers as “ex” so often that I assumed they were divorced. Then I came across an item from the Los Angeles Times dated June 10, 1942 that stated that Erickson had just filed divorce papers in Reno so that he could marry actress Margaret Hayes.

Hotel Knickerbocker c. 1930s

Frances had spent the late 1930s and early 1940s earning a reputation for being difficult, primarily due to alcoholism. In mid-October 1942 Frances was arrested in Santa Monica for driving while intoxicated and for having bright headlights in a dimout area. She was fined $250, of which she paid a portion. She was given additional time to pay the balance. When she missed the deadline for payment a bench warrant was issued for her arrest. The actress was finally located at the Hollywood Knickerbocker where the arresting officers had to use a pass key to gain entrance to her room. Frances wouldn’t leave without a fight and she had to be forcibly dressed and dragged out of the building. All the while she was shouting “Have you ever had a broken heart?”

Frances would first be diagnosed with manic depressive psychosis, and soon thereafter with paranoid schizophrenia for which she would receive insulin shock therapy (later discredited as a treatment method).

Over the next several years Frances would spend much of her time as a patient at the Western State Hospital in Washington. Frances’ autobiography “Will There Really Be A Morning?” describes her incarceration at the hospital as a brutal nightmare. I don’t know if it was intentional or not, but in Quentin Tarantino’s film “Kill Bill” the bride (Uma Thurman) awakens from a coma in a hospital to discover that a sleazy orderly has been pimping her out. Similar outrages were alleged in Frances’ autobiography (which was probably entirely ghostwritten by a friend of hers). In the book it is said that she was a sex slave for some of the doctors and male orderlies. This unsubstantiated treatment of Frances was depicted in the 1982 film “Frances” starring Jessica Lange.

In 1978 Seattle film critic William Arnold published a fictionalized, and highly sensationalized, account of Frances’ life entitled “Shadowland”. The most salacious details of Frances’ life (many of which have been accepted as fact) seem to emanate from that book.

Frances at Television City c. 1958

One of the most horrendous “facts” of Frances’ life at Western State Hospital was that she’d had a lobotomy. Transorbital lobotomies were performed at the hospital during Frances’ time there; however, there is no record that she was ever subjected to the procedure.

Frances did make a comeback of sorts as the host of a local talk show that aired in Indianapolis from 1958 to 1964. The show “Frances Farmer Presents” remained in the number one position for its time slot during the entire run.

Frances Farmer died at age 56 of esophageal cancer in 1970.

Mon 26 Oct, 2009

Betty “Ball of Fire” Rowland

Comments (0) Filed under: UncategorizedTags: 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, Betty Rowland, burlesque, Coty, L'Aimant, Minsky's

Scent, Memory, and Burlesque Queens

I don’t normally write about perfume, even though I love it, because I don’t collect it. But this past August I had an occasion to discuss perfume and burlesque with a wonderful woman who knows a great deal about both. The woman I’m talking about is none other than legendary burlesque queen, Betty “Ball of Fire” Rowland. I met her because she was a special guest on Esotouric’s “Hotel Horrors and Main Street Vice” tour.

She began her professional dancing career as a Minsky’s girl in New York city; and she may have stayed there if it hadn’t been for a crackdown on the burlesque houses beginning in 1935. The citizenry and, perhaps even more importantly, Mayor LaGuardia, considered burlesque a corrupt moral influence. The mayor and the citizens groups couldn’t shut Minksy’s down without a good reason — there would need to be a criminal charge against Abe Minsky. At last, in 1937, a dancer at Minsky’s was busted for working without her G-string and the law stepped in. New licensing regulations would allow the burlesque houses in New York to stay open, provided that they didn’t employ strippers! Not surprisingly, that bit of legalese put a bullet through the heart of burlesque in the city.

Betty and her troupe of dancers headed west to begin a limited engagement at the Follies Theater on Main Street in Los Angeles. It may have started as a limited engagement but Los Angeles audiences loved Betty and she would continue to dance at the Follies for about 15 years.

Before she was dubbed the “Ball of Fire”, Betty was known as the “littlest burlesque star”. That appellation may have described her stature (she is very petite), but “Ball of Fire” captured her spirit. Is she still a ball of fire? You bet!

Because I had an opportunity to chat with her, I decided that rather than ask her to reminisce about celebrities she’d known, or places she’d worked, I’d ask her if she’d had a signature scent, particularly something she’d worn when she performed. She seemed a little surprised by the question, saying she’d never been asked that before, but she responded instantly. Her favorite fragrance had been Coty’s L’Aimant; and it was part of her act! She told me that before she appeared on stage she’d spray a liberal amount of the cologne all over herself so that when she “worked the curtain” the scent would waft over the first few rows.

I told her that I thought it was absolutely brilliant of her to have conceived of using a fragrance in such a creative way. There has been an enormous amount of scientific research done on olfactory memory; but you don’t have to be a scientist to know that certain aromas trigger powerful personal memories. I cannot smell leaves burning without recalling my midwestern childhood.

I told her that I thought it was absolutely brilliant of her to have conceived of using a fragrance in such a creative way. There has been an enormous amount of scientific research done on olfactory memory; but you don’t have to be a scientist to know that certain aromas trigger powerful personal memories. I cannot smell leaves burning without recalling my midwestern childhood.

As far as I was concerned, autumn had officially arrived when leaves, raked into neat piles, were burned in nearly every yard in my neighborhood.

I’ll bet that there were men who saw Betty perform who subsequently carried with them forever the memory of her perfume. I wonder how many wives and girlfriends received gifts of L’Aimant from those men over the years; and I also wonder if the men knew why they’d selected that particular perfume at a counter crowded with choices.

Betty lamented that Coty had long ago discontinued her favorite scent — but if you know where to look you can still find a vintage formulation of the famous floral. I’ve ordered a bottle for Betty, and I hope it prompts her to relive some of her most precious memories.

If you’re interested in seeing one of Betty’s performances, all you need to do is to go to YouTube. I’ve also written a little different story about Betty for In SRO Land.

Fri 4 Sep, 2009

VOGUE

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: 1910s, 1920s, Perils of Pauline, silent film, WWI

Being in vogue in the 1910s

Doesn’t everyone want to be in vogue? Women in the 1910s certainly did, and one of the face powders they counted on to enhance their beauty was Vogue.

What’s playing at the Bijou?

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

The “Perils of Pearl”

Pearl White not only cheated death and escaped disaster in each of the films in the “…Pauline” series, she did a pretty fair job of cheating biographers out of the true story of her life. She had a flair for story telling, and she never let the truth get in her way. She told whoppers about her early life, at one point even telling reporters that there hadn’t been one natural death in her family in three generations and that except for herself, only her mother and one sister remained alive. It’s not clear how, or if, Pearl explained that story to her father and one of her brothers; both still very much alive at the time she told the tale!

Another story that Pearl loved to tell was how she ran away from home at a young age and joined the circus, becoming both a trapeze artist and a bareback rider (undoubtedly another of her fabrications).

Pearl didn’t really need to manufacture any drama; her real life had plenty. She was married for the first time at age 18 (in 1907) to a fellow actor, Victor Sutherland. The couple divorced a few years later.

In 1919 Pearl met and married Major Wallace McCutcheon, Jr., a WWI vet. Wallace was an occasional actor, mainly on the stage and in light comedic roles; however, the war profoundly changed him. He was one of the many young men to return to their homes suffering from shell shock (i.e. psychological trauma). Only a couple of months following their divorce in 1921, a heavily armed Wallace vanished from a private club in New York. He was found many months later, and then spent the next several years drifting. On January 4, 1928 Wallace was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in a Los Angeles rooming house. Allegedly found near his body was a bottle of bathtub gin and a note that read: “Have a drink”.

And if there wasn’t enough excitement in her personal life, there was the day-to-day excitement of shooting action pictures in New York (Pearl never worked in Hollywood), as well as performing many of her own stunts.

Pearl’s later years

Like many artists and performers, Pearl was drawn to Paris in the years following World War I. She was offered film roles, but she preferred to perform on the stage. She did make one final film in 1924 — and then starred in a few stage reviews at the Montmarte Music Hall in Paris before retiring from performing.

One true thing about Pearl was that she knew how to hold on to a dollar. While in France she invested in a successful nightclub, a resort hotel and casino in Biarritz, as well as a stable of thoroughbred race horses.

At some point she became romantically involved with a Greek businessman, Theodore Cossika, with whom she travelled around the Middle East and the Orient.

As a result of injuries she sustained during stunt work, Pearl was in chronic pain. In order to ease the pain Pearl began to drink excessively. She was hospitalized in 1933 and was given opiates, to which she became addicted.

Pearl died of cirrhosis at age 49 on August 4, 1938 in the American Hospital in Neuilly, France. She was buried in the Cimetiere de Passy.