Fri 4 Sep, 2009

VOGUE

Comments (0) Filed under: Face Powder BoxesTags: 1910s, 1920s, Perils of Pauline, silent film, WWI

Being in vogue in the 1910s

Doesn’t everyone want to be in vogue? Women in the 1910s certainly did, and one of the face powders they counted on to enhance their beauty was Vogue.

What’s playing at the Bijou?

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

The earliest ad I found for Vogue Face Powder appeared on July 12, 1914 in the Daily Review, which was a local paper in Decatur, Illinois. According to the advertisement, the purchase of a $.35 ($7.44 in current USD) box of the face powder would get you a free ticket to the Nickel Bijou! No right thinking woman could have passed up an opportunity like that. And what would have been playing on the big screen? The extremely popular serial, “The Perils of Pauline”, which debuted in 1914 and made Pearl White a star. There was a time when Pearl was even more popular than “America’s Sweetheart”, Mary Pickford!

The “Perils of Pearl”

Pearl White not only cheated death and escaped disaster in each of the films in the “…Pauline” series, she did a pretty fair job of cheating biographers out of the true story of her life. She had a flair for story telling, and she never let the truth get in her way. She told whoppers about her early life, at one point even telling reporters that there hadn’t been one natural death in her family in three generations and that except for herself, only her mother and one sister remained alive. It’s not clear how, or if, Pearl explained that story to her father and one of her brothers; both still very much alive at the time she told the tale!

Another story that Pearl loved to tell was how she ran away from home at a young age and joined the circus, becoming both a trapeze artist and a bareback rider (undoubtedly another of her fabrications).

Pearl didn’t really need to manufacture any drama; her real life had plenty. She was married for the first time at age 18 (in 1907) to a fellow actor, Victor Sutherland. The couple divorced a few years later.

In 1919 Pearl met and married Major Wallace McCutcheon, Jr., a WWI vet. Wallace was an occasional actor, mainly on the stage and in light comedic roles; however, the war profoundly changed him. He was one of the many young men to return to their homes suffering from shell shock (i.e. psychological trauma). Only a couple of months following their divorce in 1921, a heavily armed Wallace vanished from a private club in New York. He was found many months later, and then spent the next several years drifting. On January 4, 1928 Wallace was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in a Los Angeles rooming house. Allegedly found near his body was a bottle of bathtub gin and a note that read: “Have a drink”.

And if there wasn’t enough excitement in her personal life, there was the day-to-day excitement of shooting action pictures in New York (Pearl never worked in Hollywood), as well as performing many of her own stunts.

Pearl’s later years

Like many artists and performers, Pearl was drawn to Paris in the years following World War I. She was offered film roles, but she preferred to perform on the stage. She did make one final film in 1924 — and then starred in a few stage reviews at the Montmarte Music Hall in Paris before retiring from performing.

One true thing about Pearl was that she knew how to hold on to a dollar. While in France she invested in a successful nightclub, a resort hotel and casino in Biarritz, as well as a stable of thoroughbred race horses.

At some point she became romantically involved with a Greek businessman, Theodore Cossika, with whom she travelled around the Middle East and the Orient.

As a result of injuries she sustained during stunt work, Pearl was in chronic pain. In order to ease the pain Pearl began to drink excessively. She was hospitalized in 1933 and was given opiates, to which she became addicted.

Pearl died of cirrhosis at age 49 on August 4, 1938 in the American Hospital in Neuilly, France. She was buried in the Cimetiere de Passy.

While the women of the home front were keeping things on track, servicemen needed to be reminded why they were fighting, and what they were fighting for; and nothing sent a clearer message than a gorgeous pin-up picture.

While the women of the home front were keeping things on track, servicemen needed to be reminded why they were fighting, and what they were fighting for; and nothing sent a clearer message than a gorgeous pin-up picture.

It’s also helpful to have a general knowledge of popular culture during different decades because the graphics on the box very often reflect popular themes of a specific era.

It’s also helpful to have a general knowledge of popular culture during different decades because the graphics on the box very often reflect popular themes of a specific era.

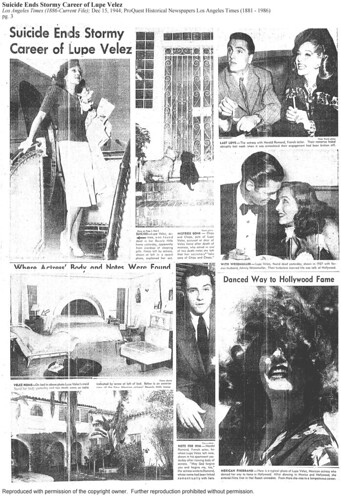

By early 1933 she was linked with Olympic champion swimmer, and star of “Tarzan, the Ape Man”, Johnny Weissmuller. On January 12th of that year she was quoted in the Los Angeles Times explaining that “Love is not for such as me, and anyone who says I am in love with Johnny Weissmuller is crazy”. It turned out that the rumors were true. Lupe and Johnny were married ten months later.

By early 1933 she was linked with Olympic champion swimmer, and star of “Tarzan, the Ape Man”, Johnny Weissmuller. On January 12th of that year she was quoted in the Los Angeles Times explaining that “Love is not for such as me, and anyone who says I am in love with Johnny Weissmuller is crazy”. It turned out that the rumors were true. Lupe and Johnny were married ten months later.

Lupe was pregnant with Harald’s child, and he was very reluctant to get married. It may have been his suggestion of a mock marriage that pushed Lupe over the edge. The note she left for him (which was reprinted in full in the papers) said as much. She wrote: “How could you Harald, fake such great love for me and our baby when all along you didn’t want us”.

Lupe was pregnant with Harald’s child, and he was very reluctant to get married. It may have been his suggestion of a mock marriage that pushed Lupe over the edge. The note she left for him (which was reprinted in full in the papers) said as much. She wrote: “How could you Harald, fake such great love for me and our baby when all along you didn’t want us”.

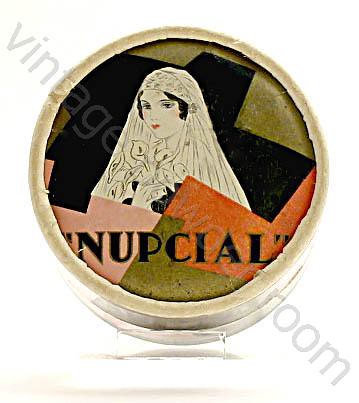

The bride in the photo looks radiant and deliriously happy, or maybe just delirious; but what about the darker side of brides? For the noir side of brides we need only to look at the 1935 film, “Bride of Frankenstein”. Elsa Lanchester may have been one of the most reluctant brides ever. She took one look at her intended mate, Boris Karloff, and let out an ear piercing shriek of terror. Not exactly an “I do”.

The bride in the photo looks radiant and deliriously happy, or maybe just delirious; but what about the darker side of brides? For the noir side of brides we need only to look at the 1935 film, “Bride of Frankenstein”. Elsa Lanchester may have been one of the most reluctant brides ever. She took one look at her intended mate, Boris Karloff, and let out an ear piercing shriek of terror. Not exactly an “I do”.

They may look benign in their beautiful gowns; with their hair perfectly coiffed and their makeup flawlessly applied, but brides can also be serial killers! The bride in Cornell Woolrich’s novel was widowed on her wedding day. She was not about to let the murderers escape justice, and the novel tracks the homicidal nearlywed as she lures, ensnares, then bumps off the five men who ruined her life. What the homicidal bride doesn’t know about the death of her groom is revealed in a contrived twist at the novel’s end.

They may look benign in their beautiful gowns; with their hair perfectly coiffed and their makeup flawlessly applied, but brides can also be serial killers! The bride in Cornell Woolrich’s novel was widowed on her wedding day. She was not about to let the murderers escape justice, and the novel tracks the homicidal nearlywed as she lures, ensnares, then bumps off the five men who ruined her life. What the homicidal bride doesn’t know about the death of her groom is revealed in a contrived twist at the novel’s end. Even in these enlightened times, wearing white and walking down the aisle with the man of your dreams seems to be a national obsession. There are TV shows devoted to brides behaving almost as badly as the woman in Woolrich’s novel. These women are the notorious “Bridezillas”. Nothing makes them happy – neither the dress, nor the catering, and perhaps not even the groom. They roar and stomp, and generally make life miserable for all those with whom they come in contact. I’d rather face a starving raptor.

Even in these enlightened times, wearing white and walking down the aisle with the man of your dreams seems to be a national obsession. There are TV shows devoted to brides behaving almost as badly as the woman in Woolrich’s novel. These women are the notorious “Bridezillas”. Nothing makes them happy – neither the dress, nor the catering, and perhaps not even the groom. They roar and stomp, and generally make life miserable for all those with whom they come in contact. I’d rather face a starving raptor.

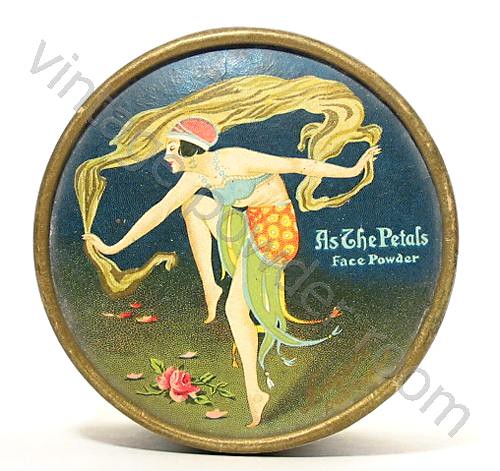

On September 14, 1927, Isadora wrapped a long hand painted silk scarf around her neck and got into a car with Italian mechanic, Benoît Falchetto. As the car pulled away Isadora waved to a group of friends, reportedly saying “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire!” (“Goodbye, my friends, I am off to glory!”). The scarf fluttered dramatically behind her, but as the car picked up speed it became entangled in the spokes of one of the wheels and tightened around Isadora’s neck. The dancer was yanked out of her seat and over the rear of the car, and then dragged along the cobblestone street to her death.

On September 14, 1927, Isadora wrapped a long hand painted silk scarf around her neck and got into a car with Italian mechanic, Benoît Falchetto. As the car pulled away Isadora waved to a group of friends, reportedly saying “Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire!” (“Goodbye, my friends, I am off to glory!”). The scarf fluttered dramatically behind her, but as the car picked up speed it became entangled in the spokes of one of the wheels and tightened around Isadora’s neck. The dancer was yanked out of her seat and over the rear of the car, and then dragged along the cobblestone street to her death.